Part V

An Ifugao woman crosses a suspension bridge on her way to collect young rice plants for transplanting into one of her family’s two paddy fields in the Philippines. Credit: Chris Stowers.

IPLC contributions to the 2050 vision

Walking to the future in the footsteps of our ancestors

The 2050 Vision of Living in Harmony with Nature expresses a profound cultural vision about a transformed relationship between humans and nature, whereby biodiversity is valued, conserved, restored, and wisely used, ecosystem services maintained, and a healthy planet delivering benefits to people.

In the 2050 Vision, the futures of nature and culture are inextricably linked, flowing inevitably from the historical co-evolution of nature and humans.

— International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity statement, August 2019, Nairobi

Nature needs urgent measures. We need to act now to protect our biodiversity. There is no more time to waste. The recognition of our rights to govern our own territories and practice our knowledge contributes to community and ecosystem resilience. As the guardians and defenders of Mother Earth, we urge all governments to act on behalf of biodiversity. See us as the most valuable part of the solution, and work together with us towards a new relationship with nature – one that heals and sustains for all of our future generations.

— International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity statement, February 2020, Rome

The six transitions widely identified by IPLCs as critical pathways in transforming current cultural, social, political, economic and technological systems to ensure their wellbeing in the 21st century, have now become imperatives for the continued health of the biosphere, as its limits are breached by modern economic growth, leading to unprecedented biodiversity loss and climate change.

Nature and culture are protected through secure IPLC land tenure and governance

IPLCs uphold life-affirming cultural relationships with nature as central to nature’s future. Cultural diversity goes hand in hand with biological diversity as they live their everyday lives in diverse ecosystems. Much of the world’s remaining biodiversity found on IPLC lands and waters has been nurtured through their distinct relationships with nature. Securing their continued guardianship of these territories and resources requires states to legally recognise and guarantee security of the collective land tenure of IPLCs, and to respect their continued governance institutions and practices.

Promoting the rights of indigenous peoples to our lands, territories, resources and governance systems, implementing ecosystem-based and culture-based solutions, as well as mainstreaming and integrating these solutions into natural and human-modified landscapes and seascapes will be vital to addressing both the biodiversity and climate crisis. In addition, ensuring our rights to customary sustainable use – especially food sovereignty – is essential for achieving all three objectives of this Convention. As rights-holders and knowledge-holders, benefit-sharing should include biological resources and ecosystems services.

— International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity closing statement, February 2020, Rome

A man holds up a small species of frog, an example of the biodiversity of the Ecuadorian rainforest. Credit: James Morgan.

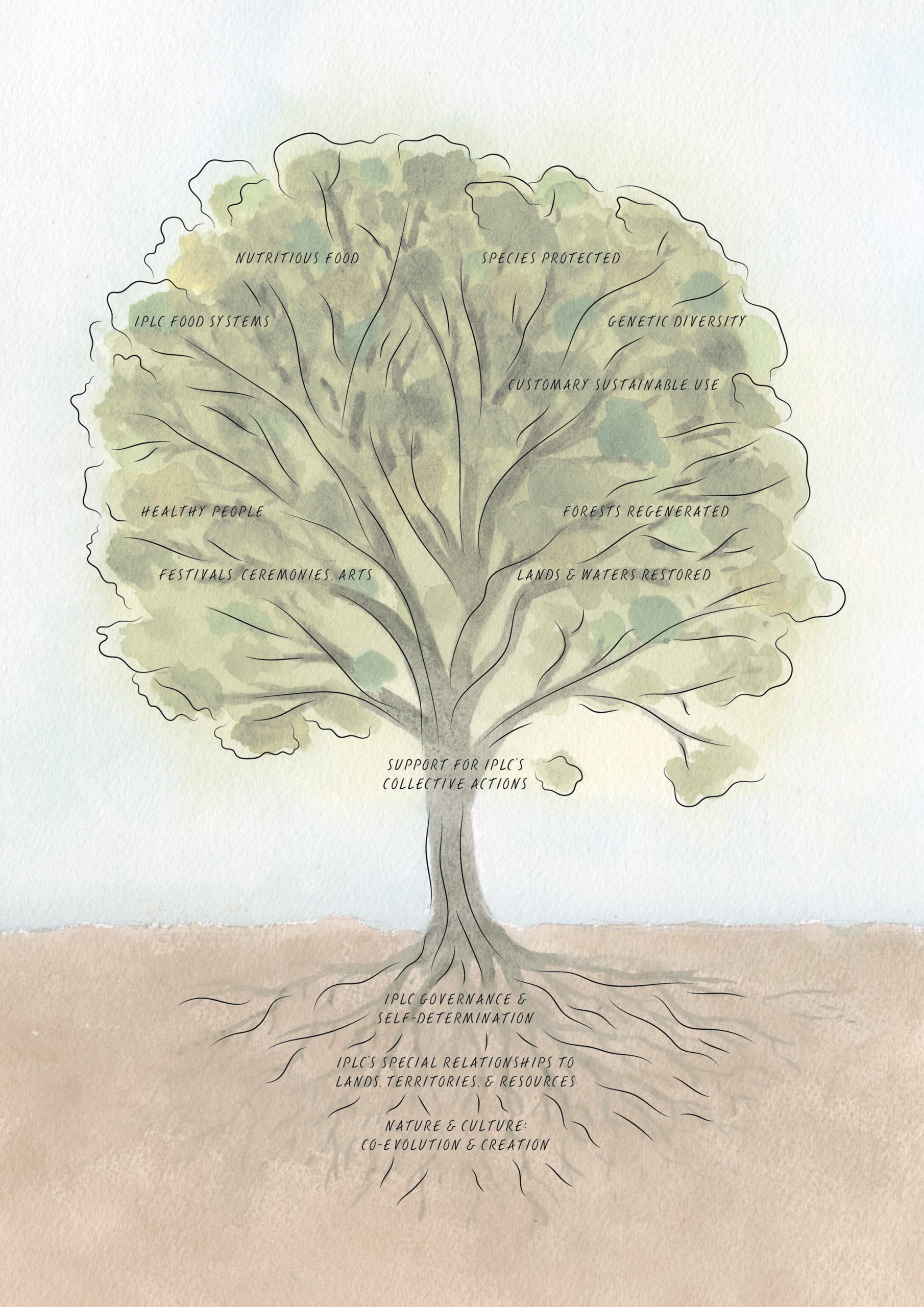

IPLC solution tree for the renewal of nature and cultures. Credit: artwork by Agnès Stienne.

IPLC collective actions will deliver multiple benefits for people and planet

Guided by their cultures and governance systems, IPLCs manage their lands and resources through customary sustainable use practices, for subsistence values and for the market. Revitalising indigenous and local food systems is considered very important for culture, biodiversity, health, for generating livelihoods for youth and women through innovative social enterprises, and for stimulating local economies which link rural and urban development.

2020 was planned as a ‘super-year’ for nature and biodiversity, including the adoption of a new, forward-looking global biodiversity strategy to 2050 at the fifteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 15) to the CBD in China. A packed schedule of biodiversity processes and events has been overtaken by the COVID-19 pandemic, an event revealing multiple interactions and profound systemic fragility in both human and natural systems. The increasing frequency of pandemics and new forms of zoonotic diseases (those that can be passed from animals to humans) caused by coronaviruses and other vectors highlights imbalances in our relationships with nature, which need addressing beyond the immediate timeframe of the current health emergency. A quick ‘return to normal’, with its multiple imbalances and vulnerabilities in human health systems, food systems, economic and trade systems, financial systems, and social and political systems, could deepen our human health and planetary crisis.

Systemic and interrelated problems are challenging humanity to explore new pathways towards the vision of living in harmony with nature by 2050, and beyond. The 2050 biodiversity strategy must envisage a future that is a radical departure from the ‘short-termism’ of quick returns to long-term holistic solutions.

The six transitions identified by IPLCs as critical pathways to transformation—in diverse ways of knowing and being, in secure land tenure, in inclusive governance, in responsible finance and incentives, in sustainable economies and in local food systems—have now become imperatives for transforming our failing social, cultural, economic, political and technological systems.

These transitions are intergenerational visions honouring the historical struggles and wisdom of past generations, drawing from the experience and innovations of today’s living generations, and embodying the legacy and hopes for future generations.

The stories and experiences shared in this report are only a sampling of the myriad actions being taken by IPLCs across the planet. Support by governments and other actors for collective actions by IPLCs could stimulate strategic partnerships for change and enable IPLCs to multiply their contributions to biodiversity conservation and sustainable use, to climate change mitigation and adaptation, and to sustainable development.

We are all future ancestors, challenged to renew the Earth for coming generations. This is humanity’s joint endeavour to save our common home.