Target 2: Biodiversity values integrated

By 2020, at the latest, biodiversity values have been integrated into national and local development and poverty reduction strategies and planning processes and are being incorporated into national accounting, as appropriate, and reporting systems.

Key messages

- Cultural and biological diversity are interdependent, and improved integration of diverse cultures and viewpoints into national and local development strategies, and into planning, accounting and reporting processes, will significantly enhance biodiversity and cultural outcomes.

- Mainstreaming holistic values requires stronger action on inclusive empowerment of IPLCs, of men and women, and of elders and youths, both as knowledge-holders and as key agents of change, innovation and transformation.

Significance of Target 2 for IPLCs

“Biological and cultural diversity are not only closely linked but also mutually reinforcing. As such, an effective mainstreaming of biodiversity into different sectors in society would also need mainstreaming culture – taking into consideration that there is diversity of culture, values and worldviews.”

— International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity1

IPLCs have been clear that effective, sustainable implementation of development goals, and mainstreaming of biodiversity values, requires being mindful of diverse cultural value systems and going beyond monetary measures of wellbeing.2

A landscape in Alta, Norway. Gunn-Britt Retter, a member of the Saami Council, says “as Indigenous Peoples we see our history and eternity, while miners and developers see money or windmills.” Credit: Anne Henriette Nilut/Saami Council.

Assessments of poverty reduction strategies highlight continuing marginalisation of the poor, including IPLCs in policy- and decision-making processes on sustainable development.3 To mainstream biodiversity values and human wellbeing across government, economic sectors and society, at all stages of planning, implementation and reporting, the empowerment of IPLCs—men and women, elders and youth—as holders of knowledge and agents of change, innovation and transformation needs to be prioritised. Including IPLCs in planning and decision-making contributes to holistic and culturally appropriate sustainable development processes and policies.

Such calls to mainstream biodiversity and cultural values in national and local planning, management and reporting processes have led to the development of various systems and frameworks aiming to facilitate this process; these, in turn, have helped to shape the regulatory policies that guide planning processes.4 At present, however, they do not adequately integrate the broader social and cultural values of biodiversity,5 and, more specifically, the value systems of IPLCs are still largely absent.6

For example, poverty reduction strategies continue to highlight the marginalisation of the “poor”, including IPLCs7, but for many IPLCs the threshold poverty line of an income of US$1.90 per day per person8 is far less salient to wellbeing than secure rights to lands, territories and resources.

Similarly, most planning processes focus on a narrow monetary approach to biodiversity values. This is often justified on the basis that monetary valuations have the most influence with decision-makers. However, this approach risks strengthening a worldview based overwhelmingly on commodity values and can deny or marginalise the importance of cultural values.9 Such a worldview is at odds with the much broader holistic values placed on nature by IPLCs and by the wider public.10

Including IPLCs, and particularly women, girls and marginalised actors, throughout the strategic planning cycle mitigates the risk of projects perpetuating inequalities and leading to unsustainable outcomes, and the risk of conflicts and harm to communities. Engaging them as partners also opens democratic space for building partnerships, ownership and legitimacy for sustainable development plans. Participatory economic, environmental, social and cultural assessments, rather than purely expert technical exercises, are able to take into account the diverse values, rights and perspectives of IPLCs, for whom material and spiritual worlds are often interwoven and imbued with use and meaning.

Contributions and experiences of IPLCs towards Target 2

IPLCs have proactively used existing planning frameworks and monitoring approaches to integrate their perspectives and values. For example, the Indigenous Navigator (see Box 4) has been developed to capture relevant, culturally sensitive data relating to both national policy commitments and local outcomes on the ground. These data can be used to highlight community needs and priorities and to ascertain whether development initiatives and planning processes are inclusive, are sensitive to context, and incorporate IPLCs’ diverse biodiversity values.

Box 4

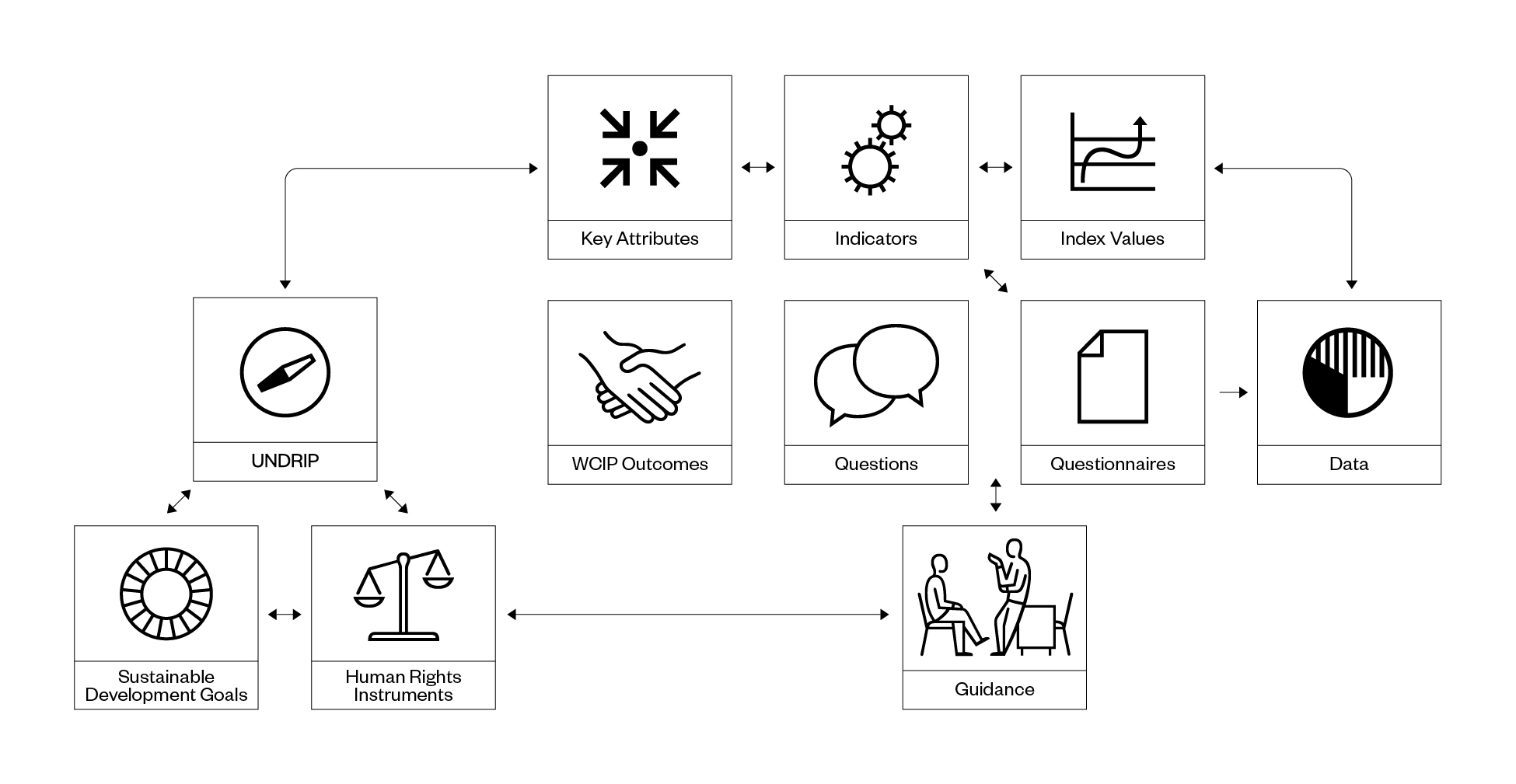

The Indigenous Navigator: monitoring outcomes of international policy instruments

The Indigenous Navigator11 is a framework and set of tools enabling indigenous peoples to monitor trends in recognition of their rights and in development. The tools include questionnaires for gathering data at the community and national levels to measure both national commitments (including implementation of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the SDGs and World Conference on Indigenous Peoples outcomes) and the actual impacts on the ground. There is also a data portal for sharing data and tools across countries and communities. Launched in 2014, the Indigenous Navigator has contributed data to indicators on self-determination; education; health; access to justice; access to lands and territories; customary law; languages; consultation and consent; participation in public life; and fundamental rights and freedom. Further development and adoption of these indicators over time will enable collection of data reflecting progress in the realisation of indigenous peoples’ rights and well-being.

Figure 1: The Indigenous Navigator monitoring framework and key tools

IPLCs have also been involved in incorporating broader values into existing and widely adopted assessment processes. For example, several Inuit communities have helped to reshape environmental impact assessments (EIAs) in the Arctic through their involvement in the Arctic Council (see Box 5 for a specific case developed in this way). Models that have been identified for meaningful engagement with indigenous peoples include indigenous-led impact assessments; impact assessments based on indigenous knowledge; and a range of thematically specific assessments, including in relation to impacts on health and ethnology, cumulative impacts, and collaborative risk mitigation. Box 5 outlines a successful example of this approach.

Box 5: Arctic Council, Sustainable Development Working Group12

Salluit, one of the Inuit communities located near Raglan Nickel Mine. Credit: Catherine Boivin.

Case study: Good practice for collaborative environmental impact assessment: Raglan Nickel Mine, northern Quebec, Canada

The Raglan Nickel Mine has been in operation since 1997. In 2016 the company proposed to extend the life of the mine by over 20 years, to 2041. A committee was formed to review the environmental and social impacts of the extension, comprised of participants from the Inuit organisation Makivik Corporation, two Inuit communities located near the project (Salluit and Kangiqsujuaq), and the proponent. Its mandate was co-developed by their respective senior leaders.

Opportunities and recommended actions

- IPLCs should continue to create and restore mechanisms to widely transmit their value systems that are based on relational values and worldviews such as a quality life.

- Governments and multilateral organisations should institutionalise improved mechanisms for meaningfully engaging and including IPLCs in all phases of development interventions, with full respect for and protection of their individual and collective rights, including the right to free, prior and informed consent.

- Governments and other actors should recognise and build on local and indigenous knowledge in the design, development and implementation of programmes related to: poverty and wellbeing; environmental assessment and management; and environmental and social monitoring of outcomes.

Key resources

- Sangha, Kamaljit, K., Russell-Smith, J. and Costanza, R. (2019) ‘Mainstreaming indigenous and local communities’ connections with nature for policy decision-making’, Global Ecology Conservation (19). Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S235198941930229X

- Arctic Council, Sustainable Development Working Group (2019) ‘Good practices for environmental impact assessment and meaningful engagement in the Arctic – Including good practice recommendations, Arctic Environmental Impact Assessment project’. Arctic Council.

References

- International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity (2020) ‘Opening Statement to the 2nd Meeting of the Open Ended Working Group on the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework’. IIFB.

- TEBTEBBA (2012) ‘Indigenous peoples’ statement’. Dialogue with Executive Coordinators, 26 March 2012, during the first round of informal negotiations of the zero draft of the outcome document. Tebtebba. Available at: http://www.tebtebba.org/index.php/content/209-indigenous-peoples-contributions-to-sustainable-development

- Cariño, J. (2005) ‘Indigenous peoples, human rights and poverty’, Indigenous Perspectives, 7(1). Tebtebba Foundation.

—

Hall, G.H. and Patrinos, H.A. (eds) (2014) Indigenous peoples, poverty, and development. Washington DC: World Bank.

—

Diana Vinding (ed) (2006) Indigenous Peoples and the Millennium Development Goals: Perspectives from communities in Bolivia, Cambodia, Cameroon, Guatemala and Nepal. ILO PRO169. - Heiner, M. et al. (2019) ‘Moving from reactive to proactive development planning to conserve Indigenous community and biodiversity values’, Environmental Impact Assessment Review 74.

- Heiner, M. et al. (2019) ‘Moving from reactive to proactive development planning to conserve Indigenous community and biodiversity values’, Environmental Impact Assessment Review 74.

- Heiner, M. et al. (2019) ‘Moving from reactive to proactive development planning to conserve Indigenous community and biodiversity values’, Environmental Impact Assessment Review 74.

—

Sangha, K., Russell-Smith, J. and Costanza, R. (2019) ‘Mainstreaming indigenous and local communities’ connections with nature for policy decision-making’, Global Ecology Conservation. - Independent Group of Scientists appointed by the Secretary-General, Global Sustainable Development Report (2019). The Future is Now – Science for Achieving Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.

- Independent Group of Scientists appointed by the Secretary-General, Global Sustainable Development Report (2019). The Future is Now – Science for Achieving Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.

- Cuckston, T. (2018) ‘Creating financial value for tropical forests by disentangling people from nature’. Accounting Forum. 42(3).

- Heiner, M. et al. (2019) ‘Moving from reactive to proactive development planning to conserve Indigenous community and biodiversity values’, Environmental Impact Assessment Review 74.

- For further information on the Indigenous Navigator, please see: ‘Find training materials, lessons learnt and inspiration for how to use the Indigenous Navigator’. 2018. Available at: http://nav.indigenousnavigator.com/index.php/en/resources-en/lessons

- Arctic Council, Sustainable Development Working Group (SDWG), Arctic Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) project (2019) ‘Good Practices for Environmental Impact Assessment and Meaningful Engagement in the Arctic – Including Good Practice Recommendations’. Arctic Council.