Part III

Biodiversity, climate change and sustainable development

Key messages

- The individual and collective actions of IPLCs are making distinctive contributions to achieving biodiversity, climate change and sustainable development goals, combining human rights and wellbeing, conservation and sustainable use of nature, and maintaining natural life-support systems. Securing the rights of IPLCs to their lands, territories and resources by 2030 will have transformative impact towards meeting the global change agenda.

- IPLCs embody intergenerational links between nature and culture, culture and development, and local to global connections, implementing the universal agenda through diverse ways of knowing and being.

- The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can serve as a tool for empowering IPLCs to overcome vulnerability and exclusion, and move towards self-determination and full and effective participation in inclusive governance.

- Given their direct material and cultural links to the environment, IPLCs are, and will continue to be, disproportionately impacted if the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and the SDGs are not met.

IPLCs and the nexus of biodiversity, climate change and sustainable development

“All countries and all stakeholders, acting in collaborative partnership, will implement this plan. We are resolved to free the human race from the tyranny of poverty and want to heal and secure our planet. We are determined to take the bold and transformative steps which are urgently needed to shift the world on to a sustainable and resilient path. As we embark on this collective journey, we pledge that no one will be left behind.”

— 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development1

Indigenous Americans march as part of Fridays for Future to highlight the impacts of climate change on their way of life. Credit: ph_m.

“This is an Agenda of unprecedented scope and significance. It is accepted by all countries and is applicable to all, taking into account different national realities, capacities and levels of development and respecting national policies and priorities. These are universal goals and targets which involve the entire world, developed and developing countries alike. They are integrated and indivisible and balance the three dimensions of sustainable development.”

— 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development2

One universal agenda and diverse ways of knowing and being

‘Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ brings together biodiversity conservation, climate change and sustainable development under a common universal agenda, but in many countries they continue to be implemented and considered in silos rather than through a holistic approach. IPLCs will continue to be disproportionately impacted if the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and SDGs are not met. Nonetheless, these goals can empower IPLCs to overcome vulnerability and exclusion, through the power of their collective actions, their self-determined development, and government support.

How does the sustainable development pledge of leaving no one behind connect with the vision of living harmony with nature by 2050, while keeping the increase in average global temperature well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels?

Paradoxically, solutions to this seemingly complex and intractable global challenge are surprisingly straightforward from the perspective of the world’s indigenous peoples. By pursuing holistic solutions from within their own values and cultures, caring for their homelands and nature3, exercising their rights to self-determined development, and promoting respect for diversity and equity among peoples, indigenous peoples are practising the core principles of sustainable development4. The more than 4,000 distinct indigenous peoples, with a collective population of about 476 million, represent the greater part of the world’s cultural diversity, and have created and speak the major share of the world’s almost 7000 languages5, and, accordingly, embody a similar breadth of humanity’s knowledge for living sustainability on Earth. Similar perspectives are advanced by many of the world’s local communities who are living with collective attachments to their territories, and collective governance and knowledge systems.

The UN General Assembly in a follow-up resolution to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,6 “[re]affirms the role of culture as an enabler of sustainable development that provides people and communities with a strong sense of identity and social cohesion and contributes to more effective and sustainable development policies and measures at all levels, and stresses in this regard that policies responsive to cultural contexts can yield better, sustainable, inclusive and equitable development outcomes.”

The following conclusions from the most recent scientific global assessments about the current state of biodiversity and climate change7

highlight the significant role of IPLCs in addressing the interrelated biodiversity, climate change and sustainable development crises:

“The challenges of mitigating and adapting to climate change while achieving food, water, energy, and health security, and overcoming the unequal burdens of environmental deterioration and biodiversity loss, all rest on a common foundation: living nature. “Specifically, we consider the fabric of life on Earth that has been ‘woven’ by natural processes over many millions of years and in conjunction with people for many thousands of years. The vital contributions made by living nature to humanity, referred to as nature’s contributions to people, affect virtually all aspects of human existence and contribute to achieving all the Sustainable Development Goals identified by the United Nations.

“Declining trends are also documented in a worldwide evaluation of 321 indicators of nature important for quality of life developed by Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Although the decline in nature is lower in areas managed by Indigenous Peoples than in other lands, ~72% of the indicators assessed show deterioration.

“The vast area of the world managed by Indigenous Peoples under various property regimes is no exception to these trends. Because of their large extent, the fact that nature is overall better preserved within them, and because of the diverse stewardship practices carried within them around the world, the fate of nature in these lands has important consequences for wider society as well as for local livelihoods, health, and knowledge transmission.”8

“Indigenous peoples have mastered the art of living on the Earth without destroying it. They continue to teach and lead by example, from the restoration of eel grass9 and salmon by the Samish Nation10, to the bison reintroduction by the Kainai Nation of the Blackfoot Confederacy11, to the restoration of traditional 800-year-old Hawaiian fish ponds12. We must heed these lessons and take on this challenging task if we want our grandchildren to have a future.”

— Jon Waterhouse, Indigenous Peoples Scholar at the Oregon Health and Science University and a National Geographic Education Fellow Emeritus and Explorer13

Mainstreaming indigenous peoples’ rights in the transformation agenda

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development entails a whole-government, whole-economy and whole-society approach. Five years after the adoption of the agenda, how well has it succeeded in engaging and mobilising all peoples on the road to transformation?

The Indigenous Peoples Major Group for Sustainable Development has reported that “Many of the Voluntary National Reports acknowledge the groups of those left behind, but do not provide mechanisms for the meaningful participation and the full inclusion of their needs and priorities. Further, many countries did not even mention indigenous peoples as distinct marginalized groups and no reference to their collective rights and contributions to sustainable development. The top-down approach to SDG implementation, the lack of policy coherence, the disconnect between State’s accountability to their human rights obligations, and the strong emphasis on economic growth are some of the key obstacles in reaching those left behind including indigenous peoples. In fact, there is a continuing lack of awareness of the SDGs at the grassroots level including in indigenous territories.”14

Indigenous peoples comprise six per cent of the global population, 15 per cent of the poorest in the world, and one third of the rural poor; they also face high levels of discrimination and are generally left behind in most countries where they live.15

While contributing the least to global warming, they suffer disproportionate impacts of climate change. Most of the world’s remaining biodiversity overlaps their lands, waters and territories, which are underpinned by their spiritual values and cultures honouring the living and sacred Earth.

IPLCs make distinctive contributions to meeting global goals in an integrated and holistic way. Placing IPLCs at the centre of implementation delivers a triple win—bringing together the fulfilment of human rights and wellbeing, the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, and the maintenance of natural ecosystems to manage climate change. Indicators on the rights and wellbeing of IPLCs constitute important measures of progress in the implementation of the global agenda for change.

Nonetheless, IPLC community-based economic, conservation, and development initiatives are contributing daily to achieving not only the Aichi Biodiversity Targets but also the SDGs and the Paris Agreement. These global goals and targets are all closely related to each other in the everyday lives of IPLCs and in their day-to-day efforts to overcome marginalisation and to assert their collective actions to solve the biosphere and climate change crisis.

In Pope Francis’s encyclical on “care for our common home”,16 he underlines the unique historical and cultural context shaping peoples’ development from within their culture:

“144. … There is a need to respect the rights of peoples and cultures, and to appreciate that the development of a social group presupposes an historical process which takes place within a cultural context and demands the constant and active involvement of local people from within their proper culture. Nor can the notion of the quality of life be imposed from without, for quality of life must be understood within the world of symbols and customs proper to each human group.

[…]

146. In this sense, it is essential to show special care for indigenous communities and their cultural traditions. They are not merely one minority among others, but should be the principal dialogue partners, especially when large projects affecting their land are proposed. For them, land is not a commodity but rather a gift from God and from their ancestors who rest there, a sacred space with which they need to interact if they are to maintain their identity and values. When they remain on their land, they themselves care for it best. Nevertheless, in various parts of the world, pressure is being put on them to abandon their homelands to make room for agricultural or mining projects which are undertaken without regard for the degradation of nature and culture.”

Indigenous peoples have stated that self-determination and sustainable development are “two sides of the same coin”,17 strongly asserting the transformative power of agency and self-determination. Rigorously applying a human-rights-based approach in the implementation of the global transformative agenda empowers the agency and voice of those currently left behind, thus overcoming the limited framework of vulnerability and marginalisation.18

Fundamentally, a human-rights approach to poverty is about empowering the poor. While the common theme underlying the experiences of poor people is one of powerlessness, human rights empower individuals and communities by granting them entitlements that give rise to legal obligations on others. Provided the poor can access and enjoy them, human rights can help to equalise the distribution and exercise of power both within and between societies. In short, human rights can mitigate the powerlessness of the poor.19

IPLC contributions to biodiversity, climate change and sustainable development

“Indigenous peoples and local communities embody humanity’s creative intelligence and wisdom in our care and love for Mother Earth. We are on the frontlines to protect the world’s remaining biodiversity, and many of our leaders have been killed defending human rights and the environment.”

International Indigenous Peoples Forum on Biodiversity at the UN Biodiversity Conference (November 2018)

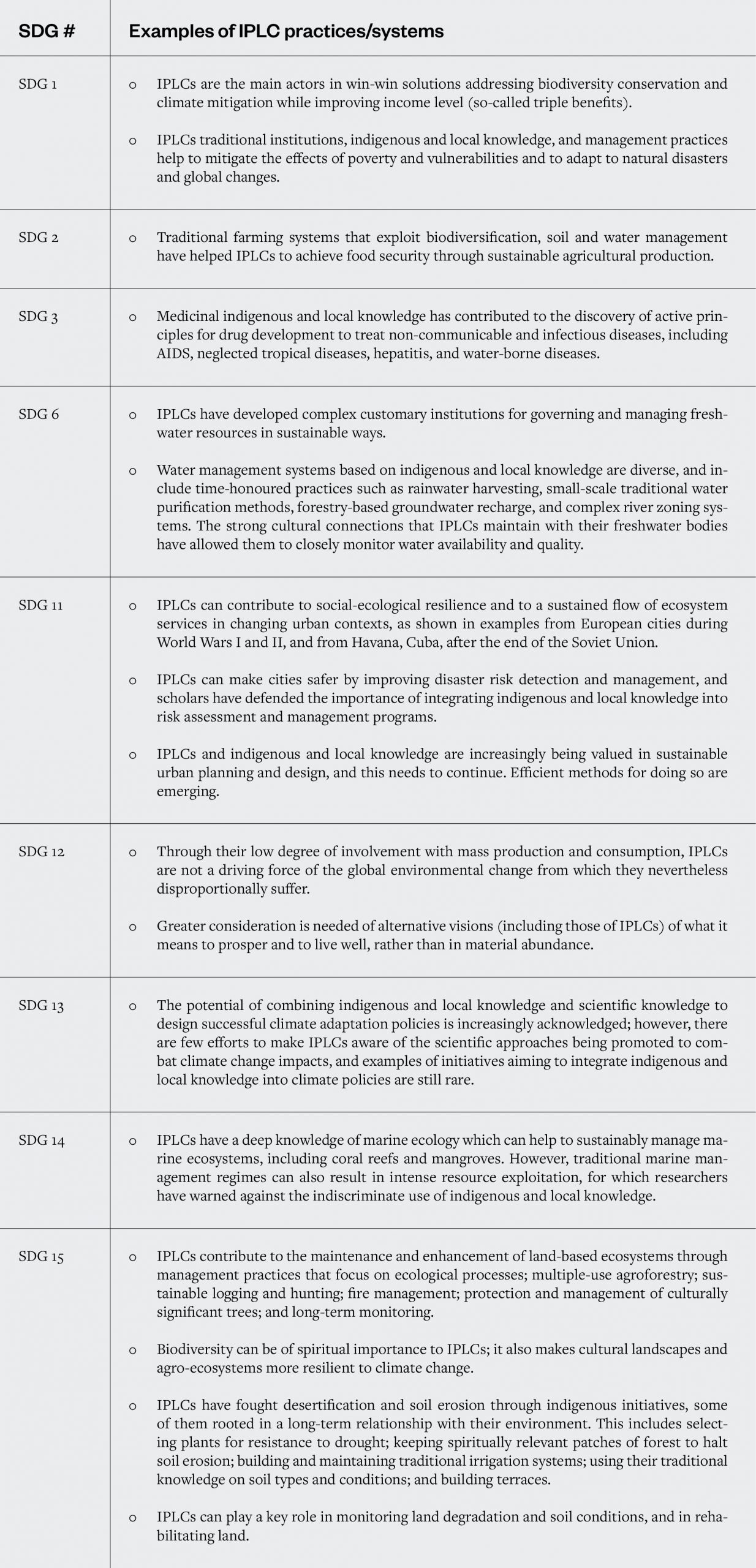

IPLC contributions to biodiversity, climate and sustainable development have started to be recognised as highly significant in global reports such as the IPBES Global Assessment on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, as compiled in Table 2, confirming and complementing IPLC experiences and many research studies documented in Part 2 of this report.

Given their direct material and cultural links to the environment, IPLCs are, and will continue to be, disproportionately impacted if the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and the SDGs are not met. Furthermore, formal incorporation of IPLCs, their many locally attuned management systems, and indigenous and local knowledge into environmental management has been shown to offer effective means to reduce environmental degradation.

Examples of negative impacts on IPLCs from insufficient progress towards meeting the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and the SDGs include:

- Continued loss of subsistence and livelihoods from ongoing deforestation (Target 5; SDG 15) and from unsustainable fishing practices (Target 6; SDG 14);

- Impacts on health from pollution and water insecurity (Target 8; SDGs 6 and 12).

Examples of IPLC contributions to sustainable environmental management include:

- Community forestry initiatives (Target 7; SDG 12);

- Traditional agriculture and aquaculture systems (Target 7; SDG 12);

- Indigenous peoples’ and community conserved territories and areas, or CCAs (Target 11; SDGs 14 and 15);

- Integration of indigenous and local knowledge into invasive and threatened species’ management (Targets 9 and 12; SDGs 14 and 15);

- Conservation of the genetic diversity of wild and domestic animals and plants through market and non-market exchanges (Target 13; SDG 2).

These contributions to the attainment of the SDGs are presented in Table 2 as informed by the IPBES Global Assessment on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

Table 2: Examples of IPLC contributions to the UN Sustainable Development Goals

Disaggregated data and community-based monitoring: the Indigenous Navigator project

A consortium of regional and international indigenous peoples’ organisations and supportive networks, human rights institutions, and the International Labour Organization (ILO), with support from the European Union, have joined forces to promote indigenous peoples’ rights through systematic generation of data on indigenous peoples’ rights and development20. The ‘Indigenous Navigator’ project21 addresses the lack of disaggregated data reflecting realities of communities to inform decision-making on policy development and implementation. The project monitors the implementation of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP); relevant international human rights conventions, including ILO No. 169; the UN SDGs; and outcomes of the World Conference on Indigenous Peoples.

“The Indigenous Navigator is a participatory monitoring tool not only on the respect of indigenous peoples’ rights but also in documenting how indigenous peoples are contributing to sustainable development through their traditional resource management practices and innovations. It will generate data to reflect the realities on the ground which can be used to make states to account and to promote the self-determined development of indigenous peoples.”

— Joan Carling, Co-convenor, Indigenous Peoples Major Group for Sustainable Development

Through the Indigenous Navigator, the significant experiences of indigenous communities from 11 countries—Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Suriname, Cameroon, Kenya, Tanzania, the Philippines, Nepal, Cambodia and Bangladesh—show how they have been addressing their priority issues and concerns.

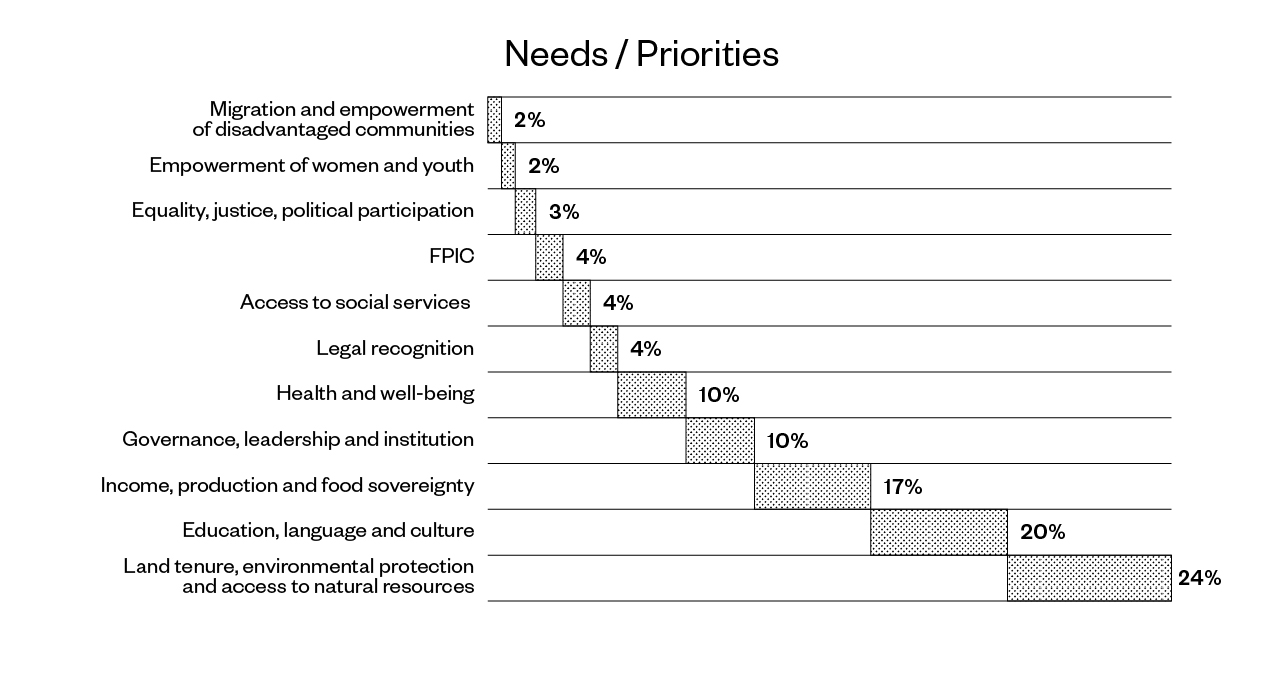

Figure 6 shows the varying needs and priorities of communities involved in the project, which were identified through community-designed projects in the 11 countries, and which include:

- Legal recognition

- Health and wellbeing

- Education, language and culture

- Income, production and food sovereignty

- Governance, leadership and institutions

- Land tenure, environmental protection and access to natural resources

- Access to social services

- Equality, justice and political participation

- Free, prior and informed consent

- Migration, and empowerment of disadvantaged communities

- Empowerment of women and youth.

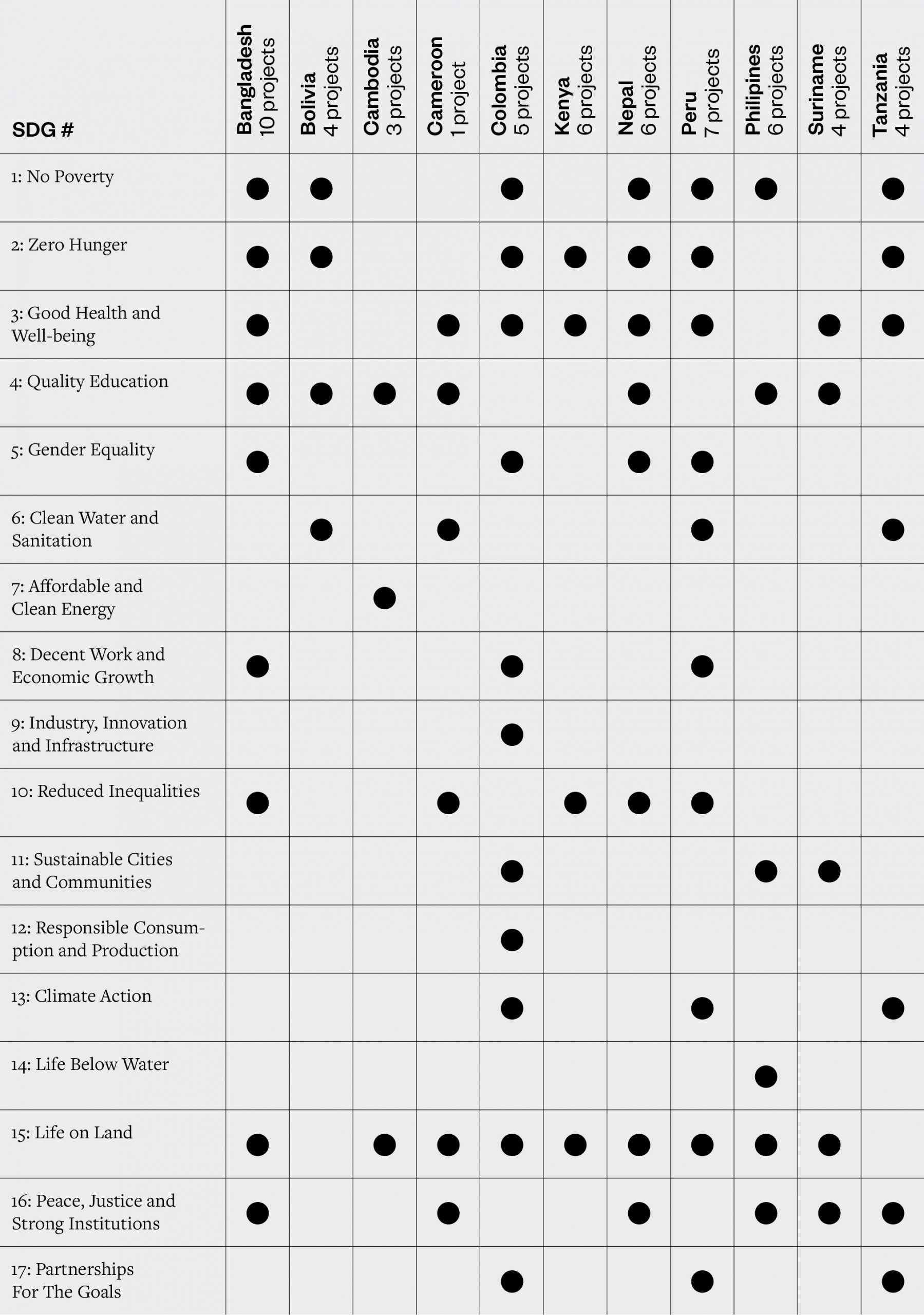

How these community needs and priorities link to the SDGs, according to 40 communities from the 11 countries implementing the Indigenous Navigator is shown in Table 3. SDG 15, Life on Land, stands out as the primary target for IPLCs. Other equally important goals relate to poverty, inequality, gender equality, quality education, good health and wellbeing. The need to deal with climate change, peace, justice and strong institutions were also considered important.22

Figure 7: Community needs and priorities identified by indigenous communities in 11 countries through the Indigenous Navigator

The Indigenous Navigator data shows that the communities are strongly affected and highly concerned about issues relating to their land tenure, environmental protection and access to natural resources (about 24 per cent); education, language and culture (20 per cent); and income, production and food sovereignty (17 per cent). Related issues, while they may appear to be of much less concern (10 per cent and below) are equally relevant to the communities.

Table 3 shows how the SDGs prioritised for implementation in the 11 countries map to their community projects (a project may relate to one or more SDGs). The Indigenous Navigator data allowed them to identify and highlight their concerns at the local, national and international level. The project development process empowered the community to generate data and to confidently engage with key stakeholders to demand policy change linked to SDGs, to climate change and to the UNDRIP. Provisions under the UNDRIP linked to SDGs include rights to self-determination; distinct customary political and economic institutions; right to development; right to spirituality; right to identity; education and transmission of knowledge; conservation and protection of environment without discrimination; and access to technical and financial assistance.

Table 3: SDGs targeted by the 11 countries implementing Indigenous Navigator projects in selected communities

Communities’ experiences with the Indigenous Navigator

The following cases show how communities in Peru and Cameroon have used the full potential of the Indigenous Navigator to generate data, analyse their situation, and come up with strategies and solutions to address their issues and concerns. In Peru, the Academy of Leaders (Sharian) of the Wampis Nation shows how the youth were inspired to emerge as leaders and knowledge-bearers (Box 49). In Cameroon, the lack of citizenship rights among the Baka, Bagyeli and Bedzang peoples starkly illustrates the knock-on impacts and restrictions on the enjoyment and exercise of economic, social and cultural rights as a ‘non-citizen’ in your own country (Box 50).

Young members of the Wampis Nation at a meeting. Credit: Pablo Lasansky.

Box 49: Shapiom Noningo, Peru Equidad

Case study: Sharian: the Wampis Academy of Leaders, Peru

The ‘Sharian Academy of Leaders’ is an initiative of the Autonomous Territorial Government of the Wampis Nation (GTANW) to cultivate young leaders who, in the future, can promote the autonomous development of the Wampis Nation based on solid knowledge of its socio-cultural elements and indigenous peoples’ human rights. It prepares leaders with an integral, holistic, broad and intercultural formation—leaders who are committed to the future vision of their people and imbued with the values of their cultural roots.

— Read the full case study

Box 50: Gbabandi, Okani and Forest Peoples Programme

Baka, Bagyeli and Bedzang women participating in a national workshop on indigenous rights and biodiversity. Credit: Adrienne Surprenant.

Case study: The right to citizenship among Baka, Bagyeli and Bedzang in Cameroon

Indigenous Baka, Bagyeli and Bedzang peoples in Cameroon have joined forces to represent themselves through a national platform of indigenous forest peoples’ organisations, under the name of Gbabandi. The communities used the Indigenous Navigator survey tools to address the lack of official data on the situation of indigenous peoples in Cameroon, prioritising the issue of citizenship under SDG Target 16.9, which aims to provide a legal identity to all, including free birth registrations, by 2030.

— Read the full case study

Opportunities and recommended actions

The first SDG Summit, charged with taking stock of progress in the first four years of implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, was held in September 2019 at UN Headquarters in New York. Accordingly, the first quadrennial global sustainable development report, entitled ‘The future is now: Science for achieving sustainable development’, authored by 15 independent scientists, was released.23

The report cautioned that recent trends show that the world is going backwards on inequality, climate change, biodiversity loss, and ecological footprint; and is increasing waste and pollution.

It states: “Some of those negative trends presage a move towards the crossing of negative tipping points, which would lead to dramatic changes in the conditions of the Earth system in ways that are irreversible on time scales meaningful for society. Recent assessments show that, under current trends, the world’s social and natural biophysical systems cannot support the aspirations for universal human well-being embedded in the Sustainable Development Goals.”

Policymakers were urged to consider the SDGs holistically, grasping the opportunity to see links between various targets and goals in the SDGs, and to further reflect on the underlying systems that need to be addressed. The report highlighted six entry points and four levers for change towards stepping up progress in implementation of the SDGs.

The six entry points:

- Human wellbeing and capabilities

- Sustainable economies

- Energy decarbonisation and access

- Food and nutrition

- Urban and peri-urban development

- Global commons.

The four levers for change:

- Governance

- Economy and finance

- Individual and collective action

- Science and technology.

Economy and finance, similar to science and technology, are to be pursued not as ends in themselves but as means to address society’s priorities. Each lever, combined with each entry point for transformation, comprises a context-specific pathway to be identified and agreed by relevant actors in different governance spaces.

The following recommendations take into account such global guidance, while linking it with the situation of IPLCs as described in this report:

- IPLCs should scale up individual and collective actions in the exercise of self-determination and sustainable development, guided by their cultural and spiritual values and care for their homelands and nature.

- IPLCs should renew and deepen holism and integration in intergenerational knowledge creation and problem-solving, promoting understanding of the linkages between: nature and culture; local and global; self-determination and partnership; and immediate and long-term actions.

- IPLCs should deepen and widen the use of community-based monitoring and information systems as a tool for self-governance, and for increased transparency and accountability of all actors at all levels, building the evidence base and knowledge for transformation, while being inclusive of elders and youth, women and men, and persons with disabilities.

- Governments and all actors should apply human rights and democratic principles at all levels of governance—ensuring holism, inclusiveness and social justice in addressing biodiversity and climate challenges—thus securing multiple benefits across society.

- All actors should develop partnerships for generating knowledge and for sustainable and equitable outcomes through: respecting and recognising indigenous and local knowledge and other knowledge systems as complementary to sciences; community participatory research; education for sustainable development; appropriate and innovative technologies; and creating multi-actor knowledge platforms.

Young members of the Wampis Nation at a meeting. Credit: Pablo Lasansky.

Key resources

- Indigenous Navigator (2017) Making the Sustainable Development Goals work for indigenous peoples via community-generated data. Baguio: Indigenous Navigator. Available at: http://nav.indigenousnavigator.com/images/Press/27-april-2017-press-release-making-the-sdgs-work-for-Indigenous-peoples.pdf

- Indigenous Peoples’ Major Group for Sustainable Development (2019) Inclusion, equality, and empowerment to achieve sustainable development: realities of indigenous peoples. Baguio City and San Francisco: Indigenous Peoples’ Major Group for Sustainable Development. Available at: https://www.indigenouspeoples-sdg.org/index.php/english/all-resources/ipmg-position-papers-and-publications/ipmg-reports/global-reports/124-inclusion-equality-and-empowerment-to-achieve-sustainable-development-realities-of-indigenous-peoples/file

- United Nations Environment Programme (2017) Indigenous people and nature: a tradition of conservation. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme. Available at: https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/indigenous-people-and-nature-tradition-conservation

- Raygorodetsky, G. (2018) Indigenous peoples defend Earth’s biodiversity – but they’re in danger. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2018/11/can-indigenous-land-stewardship-protect-biodiversity-/

References

- United Nations (n.d.) Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform. New York: United Nations. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

- United Nations (n.d.) Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform. New York: United Nations. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

- United Nations Environment Programme (2017) Indigenous people and nature: a tradition of conservation. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme. Available at: https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/indigenous-people-and-nature-tradition-conservation

- Raygorodetsky, G. (2018) ‘Indigenous peoples defend Earth’s biodiversity – but they’re in danger’ National Geographic. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2018/11/can-indigenous-land-stewardship-protect-biodiversity-/

- UNESCO (n.d.) ‘Indigenous Peoples.’ Available at: https://en.unesco.org/indigenous-peoples

- United Nations General Assembly resolution 70/L.59, Culture and sustainable development, A/C.2/70/L.59, (8 December 2015).

-

IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). Bonn, Germany: IPBES. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579

—

IPCC (2019) ‘Summary for Policymakers’, in Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Calvo Buendia, E., Masson-Delmotte, V., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Zhai, P., Slade, R., Connors, S., van Diemen, R., Ferrat, M., Haughey, E., Luz, S., Neogi, S., Pathak, M., Petzold, J., Portugal Pereira, J., Vyas, P., Huntley, E., Kissick, K., Belkacemi, M., Malley, J. (eds.) Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/chapter/summary-for-policymakers/ - Butchart, S. H. M., Miloslavich, P., Reyers, B. and Subramanian, S. M. (Draft) ‘Chapter 3. Assessing Progress towards Meeting Major International Objectives Related to Nature and Nature’s Contributions to People’, in IPBES Global Assessment on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn: IPBES.

- Northwest Treaty Tribes (2014) Suquamish Tribe, Agencies Restore Eelgrass Beds On Bainbridge Island. Northwest Treaty Tribes. Available at: https://nwtreatytribes.org/suquamish-tribe-agencies-restore-eelgrass-beds-bainbridge-island/

- Suquamish Nation (n.d.) Salmon Recovery. Suquamish: Suquamish Nation. Available at: https://suquamish.nsn.us/home/departments/fisheries/finfish/salmon-recovery/

- Morris, A. (2017) Bringing Back the Bison. Washington, D.C.: New Geographic. Available at: https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2017/05/02/bringing-back-the-bison/

- State of Hawaii (2015) Support restoration of Hawaiian fishponds through permitting, community projects, and technical assistance. Open Performance Hawaii. Available at: https://dashboard.hawaii.gov/stat/goals/25ji-kwv7/s6mu-ui3j/hymx-icse

- National Geographic (n.d.) Jon Waterhouse. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. Available at: https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/author/jwaterhouse/

- Indigenous Peoples Major Group for Sustainable Development (n.d.) Indigenous Peoples Major Group for Sustainable Development. Baguio and San Francisco: Indigenous Peoples Major Group for Sustainable Development. Available at: https://indigenouspeoples-sdg.org/index.php/english/

—

Indigenous Peoples’ Major Group for Sustainable Development (2019) Inclusion, Equality, and Empowerment to Achieve Sustainable Development: Realities of Indigenous Peoples. Baguio City and San Francisco: Indigenous Peoples’ Major Group for Sustainable Development. Available at: https://www.indigenouspeoples-sdg.org/index.php/english/all-resources/ipmg-position-papers-and-publications/ipmg-reports/global-reports/124-inclusion-equality-and-empowerment-to-achieve-sustainable-development-realities-of-indigenous-peoples/file - Hall, G. and Gandolfo, A. (2016) Poverty and exclusion among Indigenous Peoples: The global evidence. Washington, D.C.: Voices, World Bank Blogs. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/poverty-and-exclusion-among-indigenous-peoples-global-evidence

—

The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (2016) Indigenous Peoples and the 2030 Agenda. New York: The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2016/08/Indigenous-Peoples-and-the-2030-Agenda.pdf - Pope Francis (2015) Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’ of the Holy Father Francis on Care for our Common Home. Vatican: The Holy See. Available at: http://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html

- Independent Group of Scientists appointed by the Secretary-General, Global Sustainable Development Report (2019). The Future is Now – Science for Achieving Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.

- Cultural Survival (2017) ‘What do the Sustainable Development Goals mean for indigenous peoples?’ Available at: https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/what-do-sustainable-development-goals-mean-indigenous-peoples

- United Nations General Assembly (2012) Extreme poverty and human rights: Note by the Secretary-General. A/HRC/21/39. New York: United Nations General Assembly. Available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N12/458/06/PDF/N1245806.pdf?OpenElement

- Indigenous Navigator (2017) Making the Sustainable Development Goals Work for Indigenous Peoples via Community-generated Data. Baguio: Indigenous Navigator. Available at: http://nav.indigenousnavigator.com/images/Press/27-april-2017-press-release-making-the-sdgs-work-for-Indigenous-peoples.pdf

- The Indigenous Navigator is a global initiative comprised of six consortium partners: Asian Indigenous Peoples Pact, Tebtebba, International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, Forest Peoples Programme, Danish Institute for Human Rights and International Labour Organization. The tool is being piloted in 11 countries and is open for use by indigenous peoples and local communities.

- The chart provides a sense of trend and status of how IPLCs look into these matters.

- Independent Group of Scientists appointed by the Secretary-General, Global Sustainable Development Report (2019). The Future is Now – Science for Achieving Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.