Target 11: Protected and conserved areas

By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.

Key messages

- The 17 per cent and 10 per cent conservation targets are likely to be met on a purely spatial accounting basis, but progress on effectiveness and equity lags far behind. This has resulted in continued conflict with, and alienation of IPLCs, including, at times, gross human rights violations.

- IPLCs govern at least 50 per cent of the global land area, under customary or community-based regimes, with mounting evidence that in these areas biodiversity is being conserved effectively, thus revealing a major opportunity to boost conservation globally being missed under current conservation regimes.

- A radical transformation in conservation policy and practice is needed, towards rights-based and collaborative approaches that recognise the huge conservation potential of securing IPLC rights to lands and territories.

- A conceptual change is called for from ‘conservation as the objective’ of external interventions in seemingly ‘natural’ areas without human influence, towards understanding that high conservation outcomes arise from ongoing culturally rooted relationships between humans and nature, as manifested by IPLCs with their lands, territories and resources.

Significance of Target 11 for IPLCs

Target 11 is extremely important for IPLCs because, depending on how protected and conserved areas are conceptualised and implemented, they can either constitute major human rights violations and displacement, or they can recognise and support the efforts of IPLCs to conserve and sustainably manage their lands, territories and natural resources. From the perspective of IPLCs, Target 11 has proved to be an opportunity to enable positive action on indigenous and community-led or co-managed sites and conserved areas, but also a serious threat where increasing restrictions have been imposed under more conventional exclusionary protected-area models.

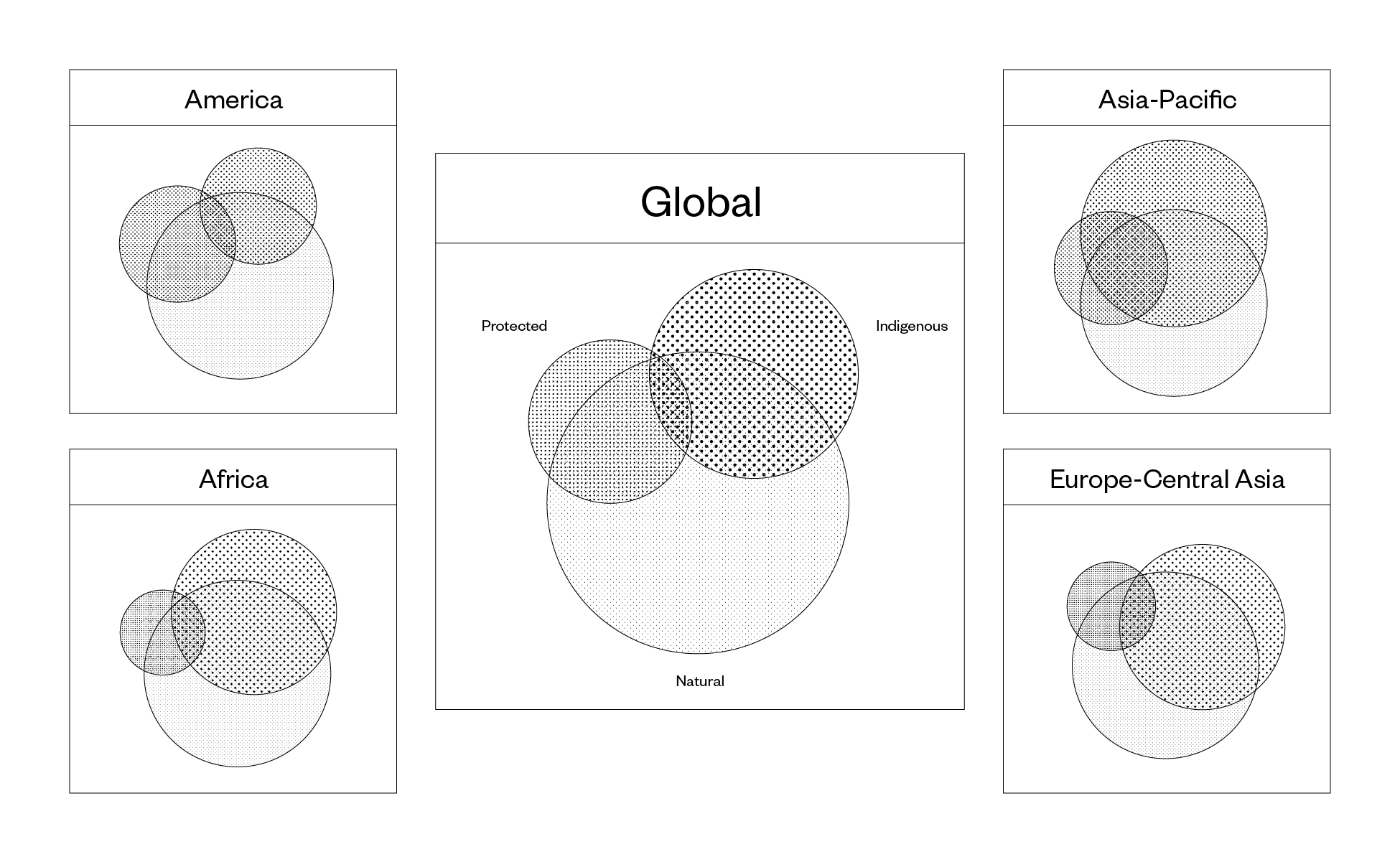

The potential contribution of recognising IPLC’s management systems and land rights to increasing the global area that is legally recognised as protected and conserved is huge. At least a quarter of the world’s land area is traditionally owned, managed, used or occupied by indigenous peoples (about 38 million square kilometres).1 This area includes about 40 per cent of all land that is formally protected, and about 40 per cent of all remaining land with ecologically intact landscapes2 and, therefore, high biodiversity and carbon storage.3

Figure 3: Overlap between the area of land formally designated protected (‘Protected’); lands traditionally owned, managed, used or occupied by indigenous peoples (‘Indigenous’); and remaining land with very low human intervention (‘Natural’); at the global and regional level

Source: Garnett, S.T. et al.4

When other forms of communal management by local communities are included, estimates of lands under the communal management of IPLCs range up to at least 50 per cent of the world’s land area, covering a wide range of biomes including forests, rangelands, deserts and coastal areas.5

Scientific evidence is now well established that much of the world’s terrestrial wild and domesticated biodiversity is on IPLC lands and territories.6 They include areas where IPLC rights are legally recognised, as well as areas where they lack legal recognition but claim, use, and manage land and resources in practice. However, these lands are subject to increasing resource extraction; commodity production; and mining, transport and energy infrastructure—all of which drive deforestation and environmental degradation.7

The need to recognise effective community conservation

Many studies confirm the value of IPLC lands for biodiversity at the national, regional and local levels. Recent research has shown that in Canada, Brazil and Australia, native vertebrate species richness is higher in indigenous-managed areas than in all other areas, including protected areas. “These comparisons confirm…that positive steps to maintain or enhance already existing values on Indigenous-managed lands have the potential to substantially advance global biodiversity conservation.”8 Thus, indigenous-managed lands are an important repository of vertebrate species richness in three of the six largest countries on Earth.9

Multiple studies have shown that deforestation rates are lower in areas where IPLC land rights are secure than in government-managed areas; and local participation in conservation management can improve biodiversity outcomes.10 A 2018 study concluded that “understanding the scale, location and nature conservation values of the lands over which indigenous peoples exercise traditional rights is central to implementation of several global conservation and climate agreements.”11

The need to recognise rights

In addition to documenting coverage of IPLC lands in relation to biodiversity, an important question is whether biodiversity on IPLC lands will be conserved into the future. Indigenous peoples strongly assert that the exercise of self-determination has historically delivered the best conservation outcomes. Evidence confirms that, while biodiversity is decreasing on all lands, it is declining less rapidly overall on indigenous peoples’ lands than elsewhere.12 Simply recognising and effectively supporting the land rights and management systems of IPLCs would greatly increase progress towards Target 11.

Conservation policy at a global level increasingly recognises the role of IPLCs in biodiversity conservation and the need to respect their rights.13 Similarly, the 2019 IPBES Global Assessment on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services emphasises the vital role of IPLCs in conservation.14 However, in many countries conservation policy, programmes and projects at the national and local levels too often remain based on outdated colonial approaches and laws enforcing ‘fortress conservation’15 and the alienation of people from nature.16 This not only fails to support IPLCs to continue to play a role in conservation, but in too many cases still generates conflict with IPLCs, severe negative socio-economic impacts, and, too often, blatant human rights abuses.17

While good progress has been made towards the quantitative conservation target of 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland waters, severe gaps remain in the implementation of the qualitative aspects of the target. Measurement of the effectiveness of government-led protected areas is patchy in terms of biodiversity outcomes,18 and assessment of the equity of governance arrangements lags far behind that which is needed to achieve this spatial target in qualitative terms.19

A conceptual change is called for from ‘conservation as the objective’ of external interventions in seemingly ‘natural’ areas without human influence, towards understanding that high conservation outcomes arise from ongoing culturally rooted relationships between humans and nature, as manifested by IPLCs with their lands, territories and resources. A radical transformation is needed from current conservation approaches that exclude and alienate IPLCs, to rights-based collaborative approaches that support and promote community-led conservation and customary sustainable use, and that celebrate the mutual relations between nature and culture.

Contributions and experiences of IPLCs towards Target 11

IPLCs are contributing significantly to achieving Target 11 in a myriad of ways and in very different national and local circumstances. Their contributions are grouped below under three headings:

- IPLC-led conservation, indigenous protected areas, and ICCAs ‘territories and areas conserved by indigenous peoples and local communities’ or territories of life)

- Collaborative management of protected areas

- Challenging human rights violations and promoting equity and justice in conservation.

The transformative conservation required in the next decade must be positively rights-affirming, going beyond outreach and collaboration towards full recognition of IPLC rights to land, territories and resources, and increased support for the many genuine instances of IPLC-led conservation.20

IPLC-led conservation

IPLC-led conservation initiatives are widespread, as documented throughout this report, yet they still receive only limited recognition and support from most governments and conservation organisations. International conservation policy (and, sometimes, national policy) can recognise these initiatives and sites as indigenous protected areas (IPAs); as ICCAs; or perhaps as other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs). IPLCs assert and insist that these areas should be recognised as ancestral lands and territories with larger meaning and purpose beyond the confines of the conservation paradigm. Indigenous peoples hold a special relationship with their territories, lands, waters and resources, which is recognised in international law as arising from customary law and practice. Alongside other political IPLC initiatives to realise their rights, advocacy linked to biodiversity and conservation is leading to reforms in national protected areas systems in several countries, including Australia (see Box 25), Canada (see Box 26) and Madagascar (Box 22) where responsive national frameworks have effectively sought to apply the achievements of global policy.

Box 25: Damein Bell, CEO, Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation

Gunditjmara rangers are restoring the environment, and revitalising their cultural heritage. Credit: Tyson Lovett-Murray, Gubdutj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC.

Case study: World Heritage listing as a tool to heal Gunditjmara Country; Budj Bim Indigenous Protected Area, Australia

The importance of our traditional homelands is inherent to our belief, culture, practice and life. The Gunditjmara community in southwest Victoria, Australia, knows that our ancestors engineered water channels, making barriers with the lava flow and stones to farm kooyang (eels) and fish. This practice continued for thousands of years to build our societies and our stone village sites.

— Read the full case study

Box 26: IISAAK OLAM Foundation, Canada

Members of Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation gather at Tsisakis (aka heel boom bay) on Meares Island in 2019 for the 35th Anniversary of the peaceful blockades that took place there in 1984 which established Meares Island as a Tribal Park. Credit: Eli Enns.

Case study: Indigenous Peoples’ Protected and Conserved Areas: The Pathway to Canada’s Target 1

In Canada, through the ‘Pathways Initiative’, indigenous peoples and governments are taking leadership together to establish indigenous protected and conserved areas (IPCAs). The ‘Pathways Initiative’ recognises the integral role of indigenous peoples as leaders in conservation, and respects the rights, responsibilities and priorities of First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples.

— Read the full case study

There is tremendous opportunity to scale up this recognition, and to replicate in other countries the successes in recognising conservation outcomes in territories and areas managed by IPLCs, and the tenure rights on which they depend. A key opportunity to achieve international commitments, including the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 and post-2020 global biodiversity framework, lies in recognising the rights of IPLCs to their lands, territories and resources, and appropriately recognising and supporting the territories and areas collectively governed, managed and conserved by IPLCs.21

→ ICCAs / Territories of life

ICCAs are inherently diverse and context-specific. Collectively, they are part of a global phenomenon more broadly called ‘territories of life’, with certain common defining characteristics:

- The community has a close and deep relationship with its territory, including through histories, worldviews, identities, cultures and ways of life.

- The community makes and enforces its own decisions and rules for its territory through a self-determined governance system, whether or not it is formally recognised by the government.

- Regardless of intentions or motivations, the community’s decisions and efforts contribute to conserving nature in the territory, as well as to its own livelihoods and wellbeing.

The global movement towards recognition of ICCAs is relatively mature and reflects many years of hard work and advocacy by indigenous peoples and community representatives. In some countries, organisations and networks of indigenous peoples and local communities have successfully engaged with governments to adopt recognition of ICCAs in national and sub-national laws and policies, including those on biodiversity, protected areas and forests.22

Efforts to highlight the crucial role of ICCAs in key international arenas have achieved important advances. The IUCN recognises four ‘governance types’ of protected areas, which includes governance by IPLCs. Meanwhile in CBD forums, ICCAs have moved from a peripheral position to a more central one, with recognition across multiple thematic and programme areas. These include protected and conserved areas; resource mobilisation; traditional knowledge and customary sustainable use; sustainable development; climate change; ecosystem restoration; and agricultural biodiversity. This broad recognition of the contributions of ICCAs, at least at a global level, has encouraged IPLCs to pursue sustainable self-determination even more powerfully, and to defend their lands and territories against the forces that threaten their survival and wellbeing.

In many countries, however, the contributions of IPLCs to conservation remain largely ‘out of sight’ of national conservation, and in many cases are still under direct threat from dominant political and economic forces. A significant gap remains between what has been agreed internationally and what is being implemented at national and sub-national levels.

The newly agreed definition of an ‘other effective area-based conservation measure’ (OECM) may help bridge this gap, though only under certain circumstances.

→ Other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs)

In 2018, at COP 14, Parties to the CBD agreed the following definition of an OECM: “A geographically defined area other than a Protected Area, which is governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in situ conservation of biodiversity with associated ecosystem functions and services and where applicable, cultural, spiritual, socio–economic, and other locally relevant values.”23 While OECMs should produce biodiversity outcomes, they do not need to be dedicated to the conservation of nature. They may, in certain circumstances, enable areas governed, managed and conserved by IPLCs to be recognised, reported and supported in ways that are more appropriate than declaring them as protected areas. How effectively this will occur depends on a range of factors, including the level of participation by IPLCs in developing national-level legal and policy frameworks for OECMs and the subsequent level of respect for the rights and responsibilities of IPLCs.24

Collaborative management of protected areas

In theory, collaborative management of protected areas has been a part of mainstream conservation policy for several decades, but in practice, the degree to which IPLCs have been empowered to participate fully and equitably has been variable. Box 27 describes an innovative example of collaborative management in Bikin National Park in the Russian Federation, where indigenous peoples are involved at all levels of management, from strategy and goal setting through to operations and monitoring.

Box 27: Polina Shulbaeva, Center for Support of Indigenous Peoples of the North

Created in 2015, Bikin National Park is is the largest protected virgin forest in Eurasia’s pre-temperate zone. Credit: Dilbara Sharipova.

Case study: Bikin National Park: innovative co-management in the Russian Federation

Bikin National Park, an area of 1,160,469 hectares in the Far East of the Russian Federation, is the largest protected virgin forest in Eurasia’s pre-temperate zone. The park was created in 201525 with objectives not only to preserve and restore the habitats of wild animals and rare species (such as the Amur tiger), but also to protect the forest culture of the indigenous peoples of this territory—the Udege and the Nanai.

— Read the full case study

Challenging human rights violations and promoting equity and justice in conservation

There are still too many cases where conservation is carried out in a coercive manner, causing negative impacts and serious human rights violations, despite widespread policy commitments to the contrary. In 2016, a report by the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples highlighted that about half of the planet’s protected areas have been established on indigenous peoples’ lands and in many cases this has been associated with violations of their human rights. The report also highlighted that conservation organisations were not doing enough to address continuing human rights violations.26 Further instances of human rights abuses have continued to come to light since then. For example:

- In February 2019, a decision by the Supreme Court of India put up to nine million people at risk of being evicted from their forest homes, in a case brought by wildlife organisations to prevent ‘encroachment’ on forest areas.27

- A water management project related to a protected area led to evictions of the Sengwer people of Kenya from their traditional territories and to the death of a Sengwer man in early 2018. Following protests and expressions of concern—which included a joint letter from the UN special rapporteurs on human rights; human rights defenders; and the rights of indigenous peoples—the European Union suspended its support for the water project and the evictions ceased.28

- In 2019, evidence emerged of human rights violations by conservation organisations operating in several parts of the world.29

Since the 1990s, conservation agencies have repeatedly been making policy commitments to uphold human rights30 and it is high time that they take definitive action to ensure that their operations fully uphold these commitments. To achieve the SDGs in synergy with the post-2020 global biodiversity framework by 2030, effective mechanisms are needed to ensure that no more human rights violations happen in the name of conservation.

At this critical juncture in the evolution and implementation of the CBD, IPLCs call for the recognition of their rights to land, territories and resources, and for the development and implementation of effective mechanisms for ensuring measurable improvements in effectiveness and equity.

Opportunities and recommended actions

- IPLCs should continue to exercise their inherent rights to self-determination and governance over their lands, waters, territories and resources according to their cultural and spiritual traditions and their reciprocal relationships with nature, and consolidate their community-based conservation.

- Governments and other actors should recognise and support the complex and enriched ecological mosaic that IPLC lands and territories deliver, with high conservation outcomes blossoming from culturally rooted approaches.

- Governments and other actors, in partnership with IPLCs, should enact appropriate legal recognition of IPLC lands and waters as a distinct land-use category contributing to conservation, in accordance with customary laws, management practices, and free, prior and informed consent.

- Governments and other actors, including conservation organisations and funding agencies, should recognise IPLCs as rights-holders and key actors in conserving biodiversity, and support them in this. This could involve, for example, support for community-led conservation models that recognise, secure and appropriately advance various types of IPLC-led conservation, including ICCAs and community conservancies, in national laws, policies and programmes.

- Governments and other actors, including conservation organisations and funding agencies, should actively uphold human rights and the fundamental principle of equity, including gender equity, as integral to conservation governance, management, strategy and programmes, in all forms of protected and conserved areas. Effective avenues to redress actions that negatively impact IPLCs should be established to restore trust and common understanding.

- Governments, IPLCs and other actors should develop collaborative platforms, partnerships and projects to achieve both conservation and human wellbeing goals, including in national and transboundary areas, World Heritage-listed sites, Ramsar sites and biosphere reserves.

Key resources

- Child, B. and Cooney, R. (2019) Local commons for global benefits: Indigenous and community-based management of wild species, forests, and drylands. A STAP document. Washington, D.C.: Global Environment Facility. Available at: http://stapgef.org/sites/default/files/publications/52954%20FINAL%20LCGB%20Report_web.pdf

- Garnett, S. T., Burgess, N.D., Fa, J.E., Fernández-Llamazares, Á., Molnár, Z., Robinson, C. J., Watson, J.E. M., Zander, K.K., Austin, B., Brondizio, E.S. et al. (2018). ‘A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation’.Nature Sustainability, 1(7), 369–374. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-0180100-6

- Tauli-Corpuz, V. (2016) Report of the Special Rapporteur of the Human Rights Council on the rights of indigenous peoples. A/71/229. New York: United Nations General Assembly. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/71/229

- Economic and Social Council of the United Nations (2019) International Expert Group Meeting on the Theme ‘Conservation and the rights of indigenous peoples.’ E/C.19/2019/7. New York: Economic and Social Council of the United Nations. Available at: https://undocs.org/E/C.19/2019/7

- ICCA Consortium: https://www.iccaconsortium.org

- Indigenous Circle of Experts (2018) We rise together: Achieving Pathway to Canada Target 1 through the creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in the spirit and practice of reconciliation. Indigenous Circle of Experts. Available at: https://www.conservation2020canada.ca/ice-resources

- Whitehead, J., Kidd, C., Perram, A., Tugendhat, H. and Kenrick, J. (2019) Transforming conservation – a rights-based approach. Moreton-in-Marsh: Forest Peoples Programme. Available at: https://www.forestpeoples.org/en/lands-forests-territories-rights-based-conservation/news-article/2019/transforming-conservation

References

- IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). Bonn, Germany: IPBES. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579

- Garnett, S. T. et al. (2018) ‘A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation’, Nature Sustainability 1(7), pp. 369–374.

- Child, B. and Cooney, R. (2019) Local commons for global benefits: Indigenous and community-based management of wild species, forests, and drylands. A STAP document. Washington, D.C.: Global Environment Facility. Available at: http://stapgef.org/sites/default/files/publications/52954%20FINAL%20LCGB%20Report_web.pdf

- Garnett, S. T. et al. (2018) ‘A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation’, Nature Sustainability 1(7), pp. 369–374.

- Child, B. and Cooney, R. (2019) Local commons for global benefits: Indigenous and community-based management of wild species, forests, and drylands. A STAP document. Washington, D.C.: Global Environment Facility. Available at: http://stapgef.org/sites/default/files/publications/52954%20FINAL%20LCGB%20Report_web.pdf

- IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). Bonn, Germany: IPBES. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579

- Child, B. and Cooney, R. (2019) Local commons for global benefits: Indigenous and community-based management of wild species, forests, and drylands. A STAP document. Washington, D.C.: Global Environment Facility. Available at: http://stapgef.org/sites/default/files/publications/52954%20FINAL%20LCGB%20Report_web.pdf

- Schuster, R., Germain, R.R., Bennett, J.R. (2019) ‘Vertebrate biodiversity on indigenous-managed lands in Australia, Brazil and Canada equals that in protected areas’. Environmental Science & Policy 101.

- University of British Columbia (2019) ‘Biodiversity highest on Indigenous-managed lands’. ScienceDaily. Available at: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/07/190731102157.htm

- Cronkleton, P., et al. (2017) ‘How do property rights reforms provide incentives for forest landscape restoration? Comparing evidence from Nepal, China and Ethiopia’, International Forestry Review 19(4), pp. 8-23.

—

Elliott, S., et al. (2019) ‘Collaboration and Conflict—Developing Forest Restoration Techniques for Northern Thailand’s Upper Watersheds Whilst Meeting the Needs of Science and Communities’, Forests 10(732).

—

Nelson, A. and Chomitz, K.M., (2011) ‘Effectiveness of Strict vs. Multiple Use Protected Areas in Reducing Tropical Forest Fires: A Global Analysis Using Matching Methods’, PLoS ONE 6(8).

—

Nepstad, D., et al. (2006) ‘Inhibition of Amazon Deforestation and Fire by Parks and Indigenous Lands’, Conservation Biology 20(1), pp. 65-73.

—

Persha, L., Agrawal, A. and Chhatre, A. (2011) ‘Social and ecological synergy: Local rulemaking, forest livelihoods, and biodiversity conservation’. Science 331(6024), pp. 1606–08.

—

Porter-Bolland, L., et al. (2012) ‘Community Managed Forests and Forest Protected Areas: An Assessment of Their Conservation Effectiveness Across the Tropics’, Forest Ecology and Management 268(6).

—

Sanchez-Azofeifa, G., et al. (2008) ‘Land cover and conservation in the area of influence of the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve, Mexico’, Forest Ecology and Management 258(6), pp. 907-912.

—

Stocks, A., et al. (2007) ‘Indigenous, Colonist, and Government Impacts on Nicaragua’s Bosawas Reserve’, Conservation Biology 21(6), pp. 1495-1505.

—

Tucker, C.,M., (2008) Changing Forests: Collective Action, Common Property, and Coffee in Honduras. Dordrecht: Springer.

—

Waller, D. M., and Reo., N.J., (2018) ‘First stewards: Ecological outcomes of forest and wildlife stewardship by indigenous peoples of Wisconsin, USA’, Ecology and Society 23(1).

—

Walker, W., Baccini, A., Schwartzman, S., Ríos, S., Oliveira-Miranda, M.A., Augusto, C., Ruiz, M.R., Arrasco, C.S., Ricardo, B., Smith, R., Meyer, C., Jintiach, J.C. and Vasquez Campos, E. (2014) ‘Forest carbon in Amazonia: The unrecognized contribution of indigenous territories and protected natural areas’. Carbon Management 5(5-6), pp. 479-485. - Garnett, S. T. et al. (2018) ‘A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation’, Nature Sustainability 1(7), pp. 369–374.

- IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). Bonn, Germany: IPBES. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579

- This is particularly evident through measures agreed at the IUCN World Parks Congress in 2003 and the CBD Programme of Work on Protected Areas in 2004; in the formation of the ‘Conservation Initiative on Human Rights’; and in several resolutions passed in subsequent World Conservation Congresses.

- IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). Bonn, Germany: IPBES. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579

- Fortress conservation is based on the belief that the best way to protect biodiversity is to fully isolate wilderness from humans under the assumption that all local and traditional land-uses contribute to biodiversity loss and degradation of the environment. See: Brockington, D. (2002) ‘Fortress Conservation: The Preservation of the Mkomazi Game Reserve, Tanzania. Melton: James Currey.

- See Rights and Resources Initiative (2018) Cornered by Protected Areas. Washington, D.C.: Rights and Resources Initiative. Available at: www.corneredbypas.com

- See, for example: Tauli-Corpuz, V. (2016) A/71/229. Report of the Special Rapporteur of the Human Rights Council on the rights of indigenous peoples. New York: United Nations General Assembly. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/71/229

—

McVeigh, K. (2019) ‘WWF accused of funding guards who “tortured and killed scores of people”’. The Guardian. London: The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/mar/04/wwf-accused-of-funding-guards-who-allegedly-tortured-killed-scores-of-people

—

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2019) EGM: Conservation and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 23-25 January 2019 Nairobi, Kenya. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/meetings-and-workshops/expert-group-meeting-on-conservation-and-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html - A recent review noted that “of the 29% of all PAs that were assessed globally, only 24% had sound management.” Source: Tauli-Corpuz, V., Alcorn, J., Molnar, A., Healy, C. and Barrow, E. (2020) ‘Cornered by PAs: Adopting rights-based approaches to enable cost-effective conservation and climate action’. World Development 130.

- Geldmann, J., Manica, A., Burgess, N.D., Coad, L and Balmford, A. (2019) ‘A global-level assessment of the effectiveness of protected areas at resisting anthropogenic pressures’. PNAS 116(46).

- Whitehead, J., Kidd, C., Perram, A., Tugenhadt, H. and Kenrick, J. (2019) ‘Transforming conservation – a rights-based approach’. Moreton-in-Marsh: Forest Peoples Programme. Available at: https://www.forestpeoples.org/en/lands-forests-territories-rights-based-conservation/news-article/2019/transforming-conservation

- For more information, see: Indigenous Peoples’ & Community Conserved Territories & Areas (n.d.) ICCA Consortium. Indigenous Peoples’ & Community Conserved Territories & Areas. Available at: https://www.iccaconsortium.org

—

Pagdee, A., Yeon-Su, K. and Daugherty, P.J. (2006) ‘What makes community forest management successful: A meta-study from community forests throughout the world’. Society & Natural Resources 19(1): 33–52. - Indigenous Peoples’ & Community Conserved Territories & Areas (n.d.) ICCA Consortium. Indigenous Peoples’ & Community Conserved Territories & Areas. Available at: https://www.iccaconsortium.org

—

IUCN-WCPA (2019) Recognising and reporting Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures. Technical Report. IUCN: Gland. - See: Convention on Biological Diversity (n.d.) ‘COP decisions.’ Available at: https://www.cbd.int/decisions/cop/?m=cop-14

- Jonas H.D., Enns E., Jonas H.C., Lee E., Tobon C., Nelson F., and K. Sander Wright (2017) ‘Will Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures increase recognition and support for ICCAs?’ PARKS 23.2. IUCN: Gland.

—

IUCN-WCPA (2019) Recognising and reporting Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures. Technical Report. IUCN: Gland. - Russian Federation (2015) ‘Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation November 3 2015 No. 1187, On the establishment of the Bikin National Park’. Moscow: Russian Federation.

- Tauli-Corpuz, V. (2016) Report of the Special Rapporteur of the Human Rights Council on the rights of indigenous peoples. A/71/229. New York: United Nations General Assembly. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/71/229

- United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (2019) ‘India must prevent the eviction of millions of forest dwellers, say UN experts’. Geneva: United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=24786&LangID=E

- Economic and Social Council of the United Nations (2019) International Expert Group Meeting on the Theme ‘Conservation and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples E/C.19/2019/7.’ New York: Economic and Social Council of the United Nations. Available at: https://undocs.org/E/C.19/2019/7

- Newing, H. and Perram, A. (2019) ‘What do you know about conservation and human rights?’ Oryx 53(4), pp. 595-596.

- Newing, H. and Perram, A. (2019) ‘What do you know about conservation and human rights?’ Oryx 53(4), pp. 595-596.