Target 20: Resource mobilization

By 2020, at the latest, the mobilization of financial resources for effectively implementing the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 from all sources, and in accordance with the consolidated and agreed process in the Strategy for Resource Mobilization, should increase substantially from the current levels. This target will be subject to changes contingent to resource needs assessments to be developed and reported by Parties.

Key messages

- The collective actions of IPLCs to conserve and sustainably use their lands and territories, and the biodiversity that these areas contain, make a substantial non-financial contribution towards the goals of the CBD.

- Funding for their actions needs to be proportionate to the scale of their contributions. It also needs to be made more accessible, through improved targeting, information-sharing and training, and culturally appropriate procedures.

- Safeguards need to be integrated into all resource mobilisation processes to bring an end to the negative impacts of biodiversity financing on the rights and livelihoods of IPLCs, and to build on the relationship between secure IPLC rights and positive biodiversity outcomes.

Significance of Target 20 for IPLCs

For IPLCs, the key issues related to Target 20 are the need for full recognition of the value of their collective actions and increase in support for these actions at a scale that is proportionate to their contributions; and the need for stronger safeguarding measures to reduce negative impacts of biodiversity financing on them.

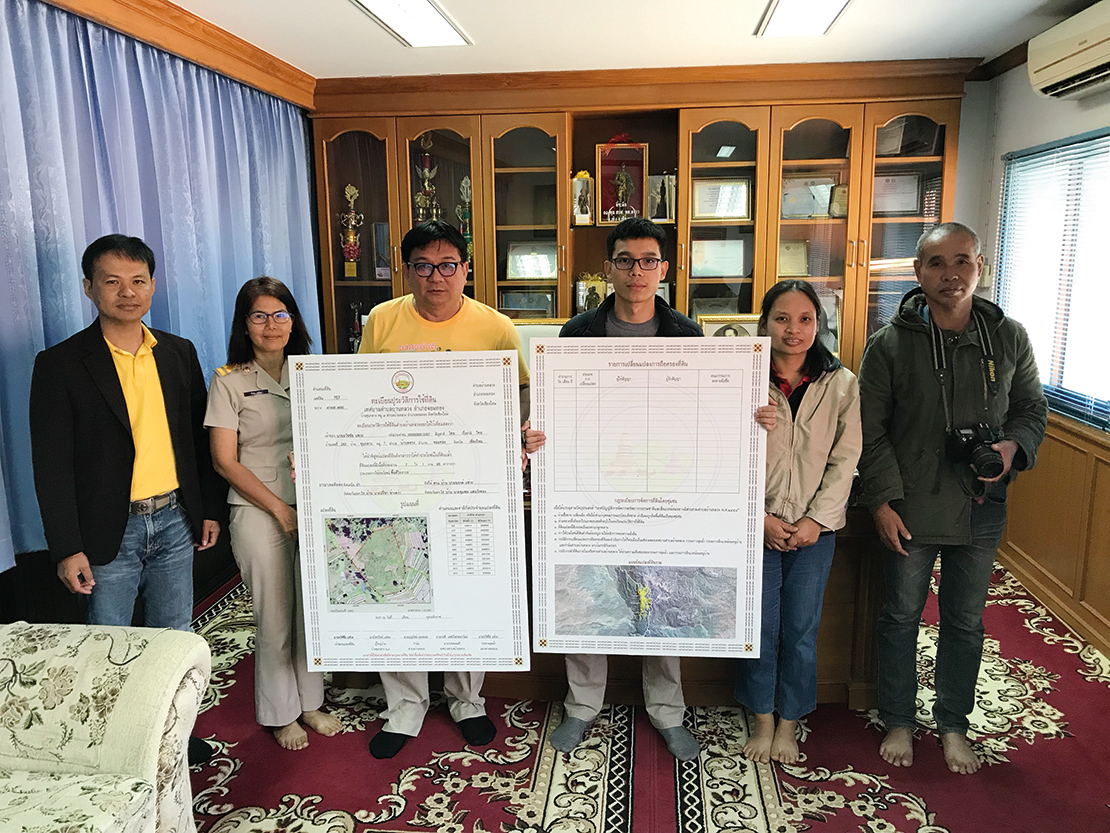

Municipal officers and community representatives illustrate local government support for community land tenure. Credit: Maurizio Farhan Ferrari.

Funding IPLCs in proportion to the scale of their contributions

Global recognition of the value of collective environmental actions has increased significantly across the work of the CBD in recent years, including in planning for the post-2020 global biodiversity framework.1 However, a lack of national reporting on support for collective actions makes it difficult to assess whether this has translated into concrete support where it matters. The CBD has tried to push for better national reporting: the CBD Financial Reporting Framework has included elements on expenditure related to IPLC collective actions since COP12 (in 2014).2 By September 2018, however, only seven countries reported having undertaken some assessment of the role of collective actions and no country indicated that a comprehensive assessment had been undertaken.3

An assessment in 2019 by the OECD estimated annual finance for global biodiversity at US$77.87 billion.4 The findings included the following points:

- Most of the funding—US$67 billion—was domestic public expenditure. Some Parties, including Canada, the EU, Norway, New Zealand and Australia, had been very supportive of allocating domestic funding to conservation by IPLCs. However, for most Parties no information was readily available on this.

- International bilateral and multilateral public expenditure related to biodiversity was estimated at US$4.9 billion per year. This includes funding through the Global Environment Facility, the Green Climate Fund, and the World Bank. Understanding how much of this expenditure is directed at IPLCs requires further in-depth review.

- Private finance was estimated to be at least US$7–10 million per year.5 The potential for private finance mechanisms (such as offsets and payments for ecosystem services) to support IPLC collective actions is not yet clear.

In summary, there is not enough evidence to assess in any detail the overall level of funding available to support IPLC collective actions. However, given that IPLCs customarily own or manage at least 50 per cent of the world’s lands, and vast marine areas, and that these areas hold a large proportion of the planet’s biodiversity6, the available information suggests strongly that the proportion of biodiversity funding available for IPLCs lags far behind their current contributions to the Aichi Biodiversity Targets.

There have been, however, some positive advances. One programme that has proven effective in many places in channelling funds to indigenous peoples and local communities for biodiversity stewardship is the Global Environment Facility’s Small Grants Programme, and the experiences of the programme offer several useful lessons (see Box 45). These lessons, however, are not universally consistent, and persistent marginalisation in some countries continues to ensure IPLCs lag in access even to proactive funding streams such as the Small Grants Programme. The Global Environment Facility’s announcement in 2019 of the new US$25 million ‘Inclusive Conservation Initiative’ dedicated to enhancing the efforts of indigenous peoples and local communities to “steward land, waters and natural resources to deliver global environmental benefits” is a welcome step.

Box 45

Case study: The Global Environment Facility’s Small Grants Programme

The Global Environment Facility’s Small Grants Programme offers grants of up to US$50,000 directly to local communities, community organisations and NGOs, including for projects related to biodiversity. A 2019 review reported the following7:

- About US$163 million has been granted to biodiversity-related projects that were either managed by indigenous organisations or by NGOs to benefit indigenous peoples. This represents 37 per cent of biodiversity projects in countries with indigenous peoples.

- The proportion of indigenous-led projects, or projects intended to benefit indigenous peoples, is increasing steadily.

- Of the indigenous-led projects, 12 per cent began with a US$5,000 ‘development grant’ to work on their project proposal. Feedback suggests that planning grants are a useful means to facilitate indigenous projects.

- Alternative forms of project proposal based on videos and photo stories have been piloted and may be useful in improving accessibility to IPLCs. However, they are challenging for programme management. Eighteen projects have been funded on this basis.

- In 2018–19, 35 per cent of participating countries had an indigenous representative on the national steering committee.

- Strategic financial partnerships with local governments, NGOs and the private sector have not only increased the total funding available but have also been found to increase the sustainability of projects, strengthen inter-institutional relations, and build awareness and appreciation of indigenous peoples’ contributions.

Safeguards in biodiversity financing

The second key issue for IPLCs in relation to Target 20 is the need to strengthen safeguarding measures to address the continued negative impacts of biodiversity financing on IPLCs. Currently, in spite of widespread recognition of the positive role of IPLCs in striving to meet the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, there are many cases where activities to progress towards these same targets are carried out in opposition to IPLCs rather than in collaboration with them, with serious impacts on their rights and livelihoods8. In response to this situation, in 2014 at COP 12 the Parties to the CBD adopted a set of voluntary guidelines on safeguards in biodiversity funding mechanisms (see Box 46) and some progress was made at subsequent COPs in developing a framework for its implementation. For IPLCs it is essential that these steps are consolidated urgently in the post-2020 framework to ensure effective safeguarding and to put an end once and for all to human rights abuses in the name of conservation.

Box 46

The CBD’s voluntary guidelines on safeguards in biodiversity financing mechanisms

In 2014, at COP 12, voluntary guidelines on safeguards in biodiversity financing mechanisms9 were adopted. They address potential impacts both on different elements of biodiversity and on the rights and livelihoods of IPLCs.

In 2018, at COP14, a checklist of safeguards was adopted based on the following overall question:

“Does the financing mechanism have a safeguard system designed to effectively avoid or mitigate its unintended impacts on the rights and livelihoods of indigenous peoples and local communities in accordance with national legislation, and to maximize its opportunities to support them?”10

A policy paper on implementation pathways for the guidelines was published by the CBD Secretariat in 201811 and contributed to discussions on a specific post-2020 safeguards framework for IPLCs, as part of the programme of work on Article 8(j). In its recommendations it reiterates the critical nature of tenure rights in safeguarding both biodiversity and human rights, and advises the development of appropriate safeguards concerning this substantive right and also of associated procedural safeguards.12

Safeguards for biodiversity and conservation funding have been introduced increasingly in international public expenditure. The Global Environment Facility introduced requirements for safeguards in 2011,13 the Green Climate Fund adopted the International Finance Corporation ‘Performance Standards’ as interim safeguards in 2014,14 and the World Bank (and all other multilateral finance institutions) have had safeguard frameworks in place since the 1990s / early 2000s. Key elements of these safeguard frameworks are prohibitions against forced resettlement, and requirements of consultation, participation and, in some cases, consent prior to activities being approved for funding.

Contributions and experiences of IPLCs towards Target 20

IPLCs make substantial contributions to all 20 of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets in the form of widespread, diverse, collective actions of the kinds that feature throughout this report. They act as environmental managers, stewards and watchdogs, in many cases on an entirely voluntary basis and under very challenging conditions. Where appropriate enabling conditions are in place, successful collective actions can spread organically through existing networks with relatively small amounts of financial support, having an impact disproportionate with the money provided. Two examples are provided in this section: one in Thailand with domestic funding from the national government (Box 47) and one in Antigua and Barbuda with funding from Global Environment Facility’s Small Grants Programme (Box 48).

Box 47: Jantanee Pichetkulsampan, Inter Mountain Peoples Education and Culture in Thailand Association

A woman gathers plants near Mae Hong Son village. Credit: V-Victory.

Case study: Local government regulations support community-led natural resource management in Thailand

In Thailand, the Municipal Ordinance Concerning Participatory Management of Natural Resources and Environment provides a legal mechanism to locally finance community-led resource management. It was passed by the Ban Luang Sub-district Municipality in Chomthong District in 2015, and San Din Daeng village, inside the Doi Inthanon National Park, was the first village to be registered for community land use under the ordinance. The financial plan for the municipality also called for mapping of neighbouring villages, which has reduced conflicts between the villages and national park authorities and brought an end to arrests for tree-felling and forest encroachment. Since then, the municipality has become a model for this kind of participatory resource management and a second municipality, Doi Kaew Sub-district, has passed a similar municipal ordinance, which is awaiting confirmation from higher policy levels.

— Read the full case study

Many IPLCs continue to receive little or no support for their actions, the support that is available is difficult to access, and they continue to face opposition, hostility and violence as they try to defend their lands and resources against unsustainable exploitation by others and also in the context of protected areas-based conservation. The adoption by the CBD of voluntary guidelines on safeguards in biodiversity financing mechanisms is an important step forward in relation to this last point, including in terms of recognising the importance of tenure over IPLC traditional territories for their survival and ways of life, and the importance of obtaining their free, prior and informed consent.

Box 48: Ruth Spencer, Global Environment Facility’s Small Grants Programme, in partnership with the Marine Ecosystems Protected Areas Trust

A group on a hike around Walling Nature Reserve. Credit: Walling Nature Reserve.

Case study: The potential impact of small grants: Global Environment Facility support for Walling Nature Reserve, Antigua and Barbuda

In Antigua and Barbuda, support from the Global Environment Facility’s Small Grants Programme for community action has led to the setting up of the Walling Nature Reserve, the first community-managed conservation site in the country. The community is working towards an effective management system through collection of entrance fees and allocation from bathroom fees, the reserve being the only rest stop in that part of the island. The government has overall responsibility to manage the area, but budgetary deficits prevent them from providing the necessary human, technical and financial resources. The Small Grants Programme has been a powerful mechanism to empower local groups and build capacity for effective community conservation and management, as well as to support community efforts related to the protected area.

— Read the full case study

Opportunities and recommended actions

- IPLCs should further document their collective actions relevant to the objectives of the CBD, including collation of case studies.

- Governments should disaggregate figures on domestic support for IPLC collective actions in national reports to the CBD. Further, international public expenditure on biodiversity conservation should be disaggregated and account for funding provided directly to IPLCs.

- The United Nations Development Programme’s Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN) should also disaggregate figures and develop a comprehensive method for governments to measure expenditure levels for biodiversity and estimate future financial needs. In addition, mechanisms should be developed to enable IPLCs to fully participate in designing policies and programmes.15

- Governments and international funding organisations should increase comprehensive, long-term, direct financial support for IPLC collective actions in line with their needs as expressed by IPLCs.16 These mechanisms should promote replication and scaling-up of successful initiatives and instruments, and should ensure improved access to funding information, including application and project timelines.

- Governments should include IPLCs on national committees with roles and responsibilities for national budgets related to domestic biodiversity financing.

- Governments and relevant actors should increase human, technical and institutional resources in relation to recognition of IPLC rights and actions—for example, advising, building capacity, improving participation and reporting—and broader forms of support for community conservation initiatives including legal, political, social and economic.

- Governments, NGOs and others should provide training on how to access funding, for women as well as men. This includes training on understanding funding guidelines, writing complex project documents, and financial management and accountability.

- Governments, international funders, and private sector funders must integrate adequate safeguards and measures related to social inclusion in all resource mobilisation processes.

A Waorani woman digs the earth with a machete in order to plant plantain saplings in a patch of ground cleared in the Ecuadorian rainforest. Credit: Karla Gachet.

Key resources

- OECD (2019) Biodiversity: Finance and the economic business case for action. Report prepared for the G7 Environment Ministers’ Meeting, 5-6 May 2019. Paris: OECD. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/environment/resources/biodiversity/G7-report-Biodiversity-Finance-and-the-Economic-and-Business-Case-for-Action.pdf

- Global Environment Facility (2019) Environmental and social safeguard standards. Washington D.C.: Global Environment Facility. Available at: https://www.thegef.org/documents/environmental-and-social-safeguard-standards

- Pérez, E.S. and Schultz, M. (2015) ‘Dialogue workshop on assessment of collective action in biodiversity conservation: Co-chairs’ summary’. Panajachel, Guatemala, 11-13 June 2015. Montreal: Convention on Biological Diversity. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/financial/micro/collective-action-report.pdf

- Swebdio (2016) ‘Collective action by Indigenous peoples and local communities’. Available at: https://swed.bio/news/collective-action-by-indigenous-peoples-and-local-communities/

References

- Convention on Biological Diversity (2016) Decision XIII/20 Resource mobilization. CBD/COP/DEC/XIII/20 (15 December 2016). Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-13/cop-13-dec-20-en.pdf

—

Convention on Biological Diversity (2019) Report of the Ad Hoc Open-Ended Inter-Sessional Working Group on article 8(J) and related provisions of the Convention on Biological Diversity, CBD/WG8j/11/L.1 (22 November 2019). Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/b4d0/f0a7/b2ea2caafcc53bffded3dc3b/wg8j-11-l-01-en.pdf

—

IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). Bonn, Germany: IPBES. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579 - Convention on Biological Diversity (2014) Decision XII/3 Resource mobilization, Voluntary guidelines on safeguards in biodiversity financing mechanisms adopted, UNEP/CBD/COP/DEC/XII/3 Annex III (17 October 2014). Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-12/cop-12-dec-03-en.pdf

- Convention on Biological Diversity (2018) Note 14/6 Resource mobilization, Further updated analysis of information provided through the financial reporting framework, CBD/COP/14/6 (30 November 2018). Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/cb4a/99a2/6829932aa5227619b998ef75/cop-14-06-en.pdf

- OECD (2019) Biodiversity: Finance and the economic and business case for action. Report prepared for the G7 Environment Ministers’ Meeting, 5-6 May 2019. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/environment/resources/biodiversity/G7-report-Biodiversity-Finance-and-the-Economic-and-Business-Case-for-Action.pdf

- The OECD review also looks at subsidies that are positive for biodiversity contributions, but these are accounted separately and are discussed in Target 3.

- IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). Bonn, Germany: IPBES. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579

- Ledwith, L. (2019) ‘Strengthening GEF SGP support to Indigenous Peoples: A review of SGP’s 25-year portfolio’. Unpublished report to the GEF SGP.

- See, for instance, Rights and Resources Initiative (2018) Cornered by Protected Areas. Washington D.C.: Rights and Resources Initiative. Available at: https://www.corneredbypas.com/

- See Convention on Biological Diversity (2014) Decision XII/3 Resource mobilization, Voluntary guidelines on safeguards in biodiversity financing mechanisms, UNEP/CBD/COP/DEC/XII/3 Annex III (17 October 2014). Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-12/cop-12-dec-03-en.pdf

- Convention on Biological Diversity (2018) Decision 14/15, Safeguards in biodiversity financing mechanisms, UNEP/CBD/COP/DEC/14/15. (30 November 2018).

- Convention on Biological Diversity (2018) Key messages from the workshop on “Biodiversity and climate change: Integrated science for coherent policy”, CBD/COP/14/INF/22 (18 October 2018).

- See page 82 of Convention on Biological Diversity (2018) Key messages from the workshop on “Biodiversity and climate change: Integrated science for coherent policy”, CBD/COP/14/INF/22 (18 October 2018).

- Since revised in 2019, see Global Environment Facility (2019) Environmental and Social Safeguard Standards. Washington D.C.: Global Environment Facility. Available at: https://www.thegef.org/documents/environmental-and-social-safeguard-standards

- Green Climate Fund (2014) Interim environmental and social safeguards of the Fund (Performance standards of the International Finance Corporation). Incehon City: Green Climate Fund. Available at: https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/interim-environmental-and-social-safeguards-fund-performance-standards-international

- van den Heuval, O., Maiden, J. and Scott, T. (2018) If we want to conserve the planet and drive sustainable growth – we need better finance for nature. Biodiversity Finance Initiative. Available at: https://www.biodiversityfinance.net/index.php/news-and-media/if-we-want-conserve-planet-and-drive-sustainable-growth-we-need-better-finance

- As indicated in post-2020 Working Group discussions which call for: “dedicated equitable and sustainable funding and financing mechanisms to support the collective actions of indigenous peoples and local communities on conservation, customary sustainable use, access and benefit sharing, restoration, and local biodiversity strategies and action plans.” Convention on Biological Diversity (2020) Report of the Global Thematic Dialogue for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities on the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, Montreal, Canada 17-18 November 2019. CBD/POST2020/WS/2019/12/2. Montreal: Convention on Biological Diversity.