Target 3: Incentives reformed

By 2020, at the latest, incentives, including subsidies, harmful to biodiversity are eliminated, phased out or reformed in order to minimise or avoid negative impacts, and positive incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity are developed and applied, consistent and in harmony with the Convention and other relevant international obligations, taking into account national socioeconomic conditions.

Key messages

- Getting subsidies and incentives right has enormous potential to turn the tide of biodiversity loss and is particularly important for IPLCs, many of whom are confronted by destructive and irresponsible investments.

- Based on available evidence, Target 3 has not been achieved. IPLCs continue to be negatively impacted by perverse subsidies that are harmful to biodiversity. They also continue to suffer from the failure to implement and increase positive incentives.

- Radical action is required urgently to upscale and mainstream effective incentives and to phase out incentives that are harmful to nature and people.

Significance of Target 3 for IPLCs

IPLCs rely on nature for their daily needs1 and, therefore, perverse subsidies such as those related to large-scale agriculture, infrastructure, chemical pollutants and land clearance have direct harmful impacts on their livelihoods and wellbeing, and, most fundamentally, on their right to life. Reforming incentives, then, is of critical importance to IPLCs and is of the utmost urgency.

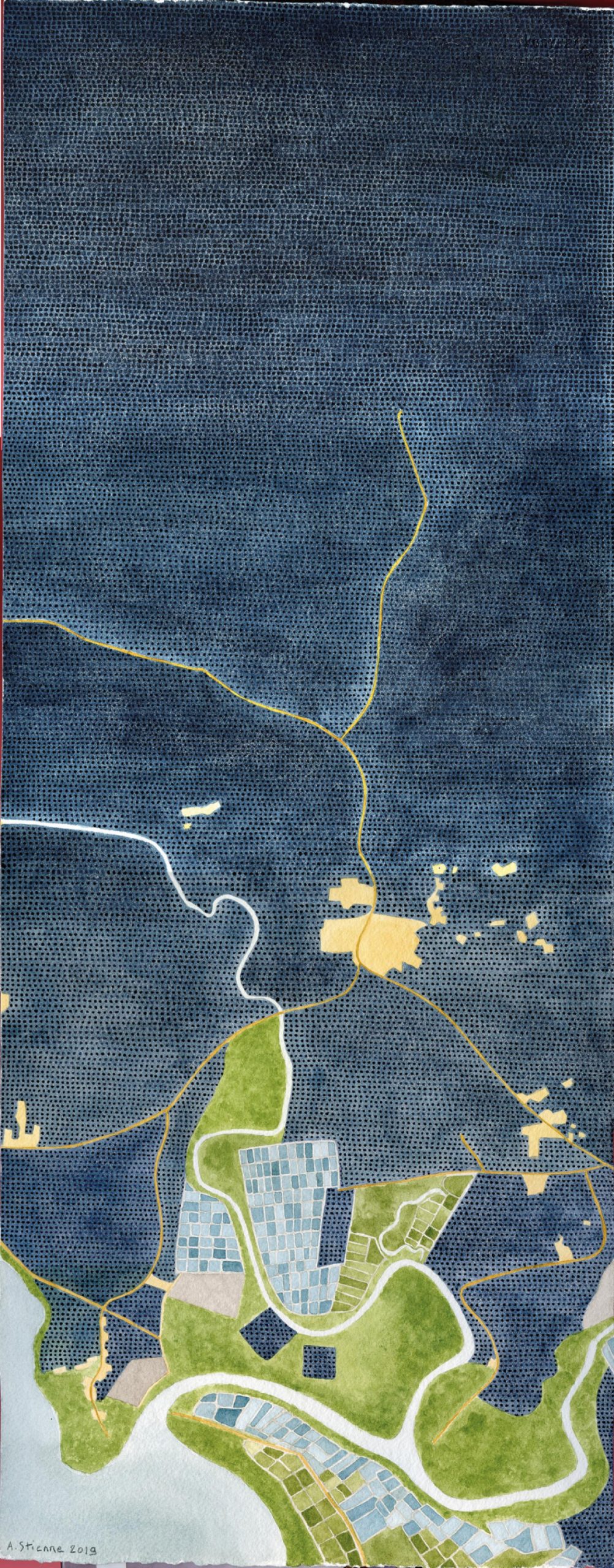

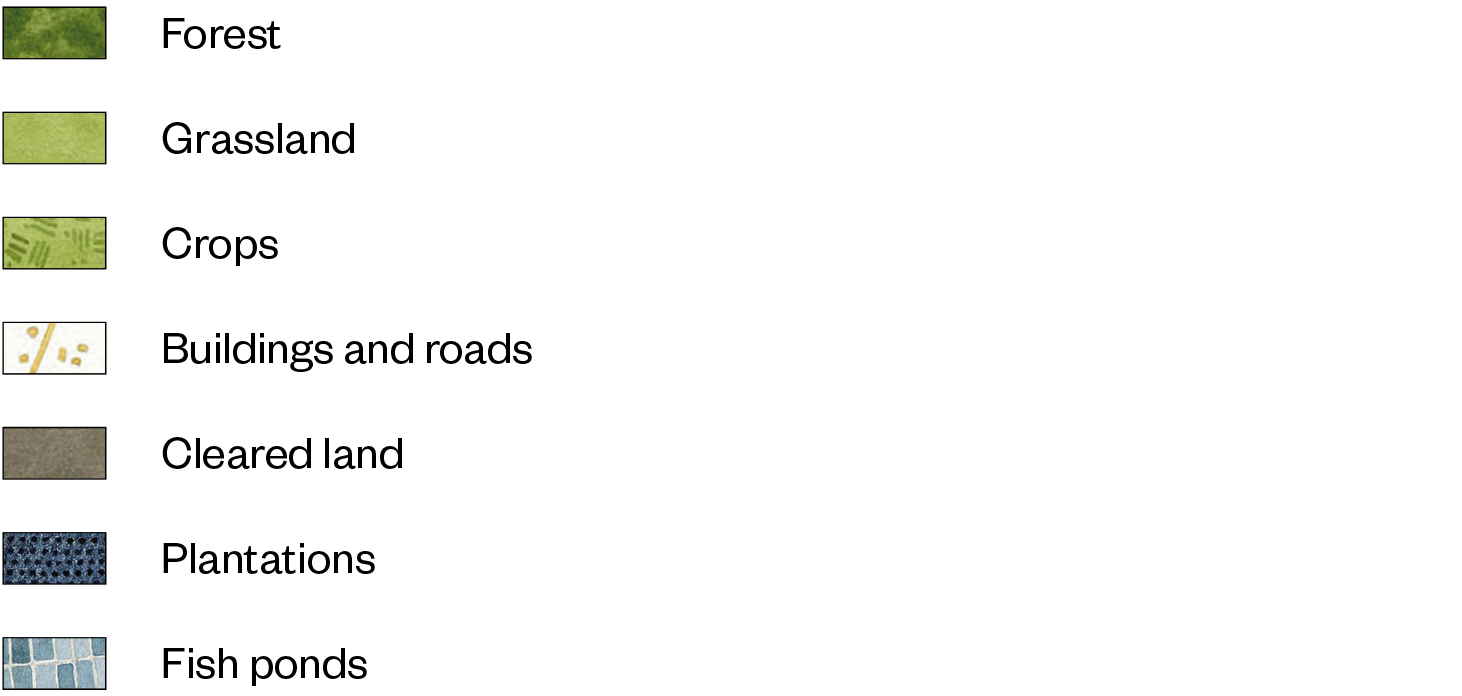

The geography of palm oil: landscape change in progress in Malaysia. Credit: Agnès Stienne, Dépaysages de palmiers à huile, Visionscarto.net.

The CBD defines harmful incentives as “measures, policies or practices that induce behaviour that is harmful to biodiversity”2 and positive incentives as “economic, legal or institutional measures designed to encourage beneficial activities.”3 Currently, harmful incentives continue to dwarf funding for biodiversity: in 2019, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimated subsidies harmful to biodiversity at US$500 billion a year, which is about 10 times the estimated global funding for biodiversity conservation and sustainable use.4 A further US$1,753 billion is spent annually on military expenditure, which could be put to much better social and environmental use.

While more research is needed to understand the effects of harmful incentives, these figures highlight the scale of reform that is needed to achieve Target 3. However, to date few governments have even identified the relevant incentives, let alone worked to reform them.5

Currently, far more resources are available for activities that drive biological and cultural diversity loss than for activities that maintain, strengthen and revitalise them. These activities include focusing on market-based solutions and technological fixes that have a strong likelihood of generating further damage rather than addressing underlying causes and systemic change. Examples of such controversial ‘solutions’ include carbon trading, geo-engineering, synthetic biology and gene drives. A major shift in investments, incentives and funding, including on technology assessments, is needed to support activities, especially through the collective actions of IPLCs, and appropriate technologies that benefit both nature and people.

Contributions and experiences of IPLCs towards Target 3

Harmful incentives

IPLCs around the world are working to raise awareness of, and to address, harmful incentives.

Examples of harmful incentives:

- New subsidies for burning wood pulp could increase deforestation of IPLC lands and territories.6

- New subsidies for expanding damaging extractive industries for energy transition in the so-called ‘Green New Deals’, which are proposed transformational reforms to tackle climate change.7

- Brazil subsidises deforestation-linked industries by an estimated US$14 billion per year while also spending US$158 million a year on preventing deforestation.8

- The World Bank continues to prop up the continued use of fossil fuels and—through development policy loans—to fund infrastructure in primary forests while also working to reduce deforestation through other initiatives.9

Examples of IPLC actions to address some of these harmful incentives:

- The European Union Renewable Energy Directive (2009/28/EC) has driven palm oil imports to the EU by encouraging greater use of biofuels.10 IPLCs have raised awareness of the significant impacts that this directive has had on their ways of life, their lands and territories, and on biodiversity.11

- IPLCs are active in resisting fossil fuel expansion, both on the ground and at the global level.12 In one of the most recent examples, in March 2020 a US federal court struck down permits for the controversial Dakota Access Pipeline and ordered a comprehensive environmental review, as a result of action by the Standing Rock Sioux to defend their ancestral homeland from risks of oil spills.13

- IPLCs have been at the forefront of civil society efforts to mitigate the effects of new tax incentives in Colombia for biofuel production from oil palm and sugar cane, and policies in Peru that encourage biofuel plantations, industrial agriculture and mega-infrastructure projects in contradiction with Peru’s zero-deforestation pledges.14

Early morning at Oceti Sakowin Camp, one of the protest camps formed to block the development of the Dakota Access Pipeine in the USA. Credit: Photo Image.

Positive incentives

Positive incentives span a wide range of activities but tend to fall into two broad categories: those focused on mitigating climate change or other environmental issues, and those focused on supporting small-scale producers. Positive incentive systems that aim to address environmental problems—such as REDD+, and payments for ecosystems services—can benefit IPLCs, but in practice their impacts have been mixed both for biodiversity and for people15, including IPLC women16 The following examples demonstrate IPLC engagement in working to ensure that positive incentives benefit people:

- In Guyana, after concerted lobbying from indigenous communities, the ‘Amerindian Land Titling’ project, funded by REDD+, has sought to deal with outstanding territorial claims and land title applications before climate investments go ahead.17

- Another REDD+ programme, Colombia’s Vision Amazonia 2020, contains a component for extending the title boundaries of indigenous land, although Amazonian indigenous peoples’ organisations have criticised it for failing to apply safeguards.18

- In Peru, climate-change-related financing from the World Bank has been linked to ambitious land titling and land rights objectives for indigenous peoples, and in those projects run by indigenous peoples’ organisations, impressive gains were made in registration of titles between 2011 and 2018.19

Recent research also highlights that REDD+ can be made more effective through early planning, up-front investment, the collection of baseline data, and rigorous and widespread monitoring of impacts.20

Box 6: Vu Thi Hien, Centre of Research and Development in Upland Areas, Vietnam, and Grace Balawag, Tebtebba Foundation, Philippines

Monitoring in process.

Case study: Getting REDD+ to work for IPLCs in Vietnam

In a pilot project in north Vietnam, Tebtebba and the Centre of Research and Development in Upland Areas worked to test whether REDD+ financial incentive systems for carbon sequestration could be developed based on respect for the wishes, rights—including gender and ethnic equality and sensitivity—and traditional knowledge of IPLCs.

— Read the full case study

With certain preconditions, such as secure tenure rights, positive incentives focused on supporting small-scale producers could safeguard IPLC livelihoods and cultural identities while also protecting the biodiversity on their lands and territories.21

Good examples of positive incentives:

- The Forest and Farm Facility in Yen Bai Province, Vietnam, supports the members of the Vietnam Farmers Union to grow cinnamon, star anise, plants for herbal medicine, and mulberry for silkworm farms. The farmers market their products collectively and have worked together to learn and apply organic growing techniques. In 2019, a US$3.5 million cinnamon processing factory was completed so that the cooperatives can supply organic cinnamon to the global market. This level of investment for forest-based organic products protects biodiversity within the harvesting areas.22

- The ‘Mountain Partnership Products Initiative’, supported by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), promotes native crops cultivated by small-scale farmers in remote areas, and has developed (with Slow Food) a voluntary product-labelling scheme.23

- The Non-Timber Forest Products Exchange Programme supports forest-based communities in Asia by helping them develop enterprises based on forest products. Efforts include assisting with a certification scheme for rattan production in Indonesia and marketing sustainable, handwoven eco-textiles in the Philippines and Indonesia.

Working in the forest. Credit: Cong Duong Hoang.

- The ‘International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative’—launched at the tenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the CBD (COP 10) and significantly expanded since then—supports the maintenance, revitalisation and strengthening of locally evolved and adapted socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes, including IPLC efforts and projects aimed at nurturing traditions and culture and maintaining ecosystems while improving local economies.

- The Right Energy Partnership is a unique collaboration between indigenous peoples and other stakeholders to deliver energy access and support the development of appropriate, rights-based renewable energy, contributing to SDG 7 (Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all); the empowerment of indigenous women and communities; and global climate action.24

Despite some good examples, given the relative invisibility of small-scale farmers and producers, including indigenous peoples, in the global economy, as evidenced in Target 7 and 13, the necessary incentives are not always available.25

Opportunities and recommended actions

- IPLCs, their supporters and other actors should explore opportunities to work in partnership with new financial actors, particularly financial institutions and private investors, both to ensure harmful subsidies such as those for fossil fuels are phased out and to support the scaling-up of local farm and forest production, community social enterprises, diverse local economies and other transition initiatives.

- Governments should set progressive percentage targets for redirecting finance from perverse subsidies to positive incentives by 2025 and 2030, and direct COVID-19 pandemic responses into opportunities to reshape the economy towards sustainability for people and planet.

- Governments and relevant actors should ensure that positive incentive systems related to climate change or the environment are created with the full and effective participation of IPLCs, have the flexibility to build the capacity of locally controlled sustainable enterprises, and have adequate safeguarding systems in place.

- Governments and relevant actors should embed technology assessments at all levels of biodiversity policy, planning and implementation.

- Governments and relevant actors should facilitate input from IPLCs in addressing Target 3, based on their traditional knowledge, practices and innovations, and also in key related processes including SDGs 2, 5, 7 and 15; the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; and trade negotiations where relevant incentives are considered.

Key resources

- Macqueen, D., Bolin, A., Greijmans, M., Grouwels, S. and Humphries, S. (2020) ‘Innovations towards prosperity emerging in locally controlled forest business models and prospects for scaling up’, World Development 125.

- Convention on Biological Diversity (2011) Incentive measures for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity: Case studies and lessons learned. Montreal: Convention on Biological Diversity. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-56-en.pdf

- Carino, J. and Sriskanthan, G. (2018). Renewable Energy & Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous Peoples Major Group for Sustainable Development. Available at: https://www.indigenouspeoples-sdg.org/index.php/english/all-resources/ipmg-position-papers-and-publications/ipmg-submission-interventions/93-renewable-energy-indigenous-peoples/file

References

- Rundle, H. (2019) ‘Indigenous knowledge can help solve the biodiversity crisis’. Scientific American. Available at: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/indigenous-knowledge-can-help-solve-the-biodiversity-crisis/

—

IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). Bonn, Germany: IPBES. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579 - Convention on Biological Diversity (n.d.) Harmful Incentives and their elimination, phase out, or reform. Montreal: Convention on Biological Diversity. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/incentives/perverse.shtml

- Convention on Biological Diversity (n.d.) Positive incentive measures. Montreal: Convention on Biological Diversity. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/incentives/positive.shtml

- OECD (2019) Biodiversity: Finance and the economic business case for action. Report prepared for the G7 Environment Ministers’ Meeting, 5-6 May 2019. Paris: OECD. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/environment/resources/biodiversity/G7-report-Biodiversity-Finance-and-the-Economic-and-Business-Case-for-Action.pdf

—

Dempsey, J., Martin, T. G. and Sumaila, U. R. (2020) ‘Subsidizing extinction?’, Conservation Letters 13(1), pp. 11-13. - Dempsey, J., Martin, T. G. and Sumaila, U. R. (2020) ‘Subsidizing extinction?’, Conservation Letters 13(1), pp. 11-13.

- Kuhlmann, W. and Putt, P. (2018) Are forests the new coal? A global threat map of biomass energy development. Asheville: Environmental Paper Network. Available at: https://environmentalpaper.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Threat-Map-Briefing-Are-Forests-the-New-Coal-01.pdf

- Kuhlmann, W. and Putt, P. (2018) Are forests the new coal? A global threat map of biomass energy development. Asheville: Environmental Paper Network. Available at: https://environmentalpaper.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Threat-Map-Briefing-Are-Forests-the-New-Coal-01.pdf

—

Auciello, B. H. (2019) A Just(ice) transition is a post-extractive transition: Centering the extractive frontier in climate justice. London: War on Want and London Mining Network. Available at: https://waronwant.org/sites/default/files/Post-Extractivist_Transition_WEB_0.pdf - McFarland, W., Whitley, S. and Kissinger, G. (2015) Subsidies to key commodities driving forest loss: Implications for private climate finance. London: Overseas Development Institute. Available at: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/9577.pdf

- Mainhardt, H. (2017) ‘World Bank development policy finance props up fossil fuels and exacerbates climate change: findings from Peru, Indonesia, Egypt and Mozambique’. Washington D.C.: Bank Information Centre. Available at: https://www.re-course.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Study-2-Executive-Summary-of-DPL-reports.pdf

- White, S. (2017) ‘More than half of EU biodiesel made from imported crops, study finds’. Brussels: EURACTIV. Available at: https://www.euractiv.com/section/agriculture-food/news/more-than-half-of-eu-biodiesel-made-from-imported-crops-study-finds/

- Forest Peoples Programme (2016) ‘EU tour by indigenous, community and NGO leaders highlights impacts of palm oil supply chains on communities and their lands and forests’. Moreton-in-Marsh: Forest Peoples Programme. Available at: https://www.forestpeoples.org/en/enewsletters/fpp-e-newsletter-august-2016/news/2016/07/eu-tour-indigenous-community-and-ngo-leaders-

—

Forest Peoples Programme (2018) ‘Indigenous peoples and forest defenders defy murder and intimidation to call on European governments to uphold their human rights commitments and tackle deforestation commodities’. Moreton-in-Marsh: Forest Peoples Programme. Available at: https://www.forestpeoples.org/en/climate-forests-redd-and-related-initiatives-global-finance-trade-public-sector-european-union-and - LeBlanc, J. (2019) ‘Indigenous-led movement to stop fossil fuels’. Washington D.C.: The Hill. Available at: https://thehill.com/opinion/energy-environment/444574-indigenous-led-movement-to-stop-the-fossil-fuels.

—

Bassey, N. (2015) ‘We thought it was oil but it was blood: Resistance to the military-corporate wedlock in Nigeria and beyond’, in: The Secure and the Dispossessed – How the Military and Corporations are Shaping a Climate-changed World. London: Pluto Press. - Lakhani, N. (2020) ‘Dakota access pipeline: court strikes down permits in victory for Standing Rock Sioux’. The Guardian. London: The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/mar/25/dakota-access-pipeline-permits-court-standing-rock

- Espinoza Llanos, R. and Feather, C. (2011) ‘The reality of REDD+ in Peru: Between theory and practice’. Moreton-in-Marsh: Forest Peoples Programme. Available at: http://www.forestpeoples.org/sites/fpp/files/publication/2011/11/reality-redd-peru-between-theory-and-practice-november-2011.pdf

- Bayrak, M.M. and Marafa, L.M. (2016) ‘Ten years of REDD+: A critical review of the impact of REDD+ on forest-dependent communities’. Sustainability 8(7), p. 620.

—

Lovera-Bilderbeek S. (2019) Agents, assumptions and motivations behind REDD+: Creating an international forest regime. Edward Elgar Publishing. - Angelsen, A., Martius, C., de Sy, V., Duchelle, A.E., Larson, A.M. and Pham, T.T. (2018) Transforming REDD+: Lessons and new directions. Bogor: CIFOR. Available at: https://cifor.org/knowledge/publication/7045

- Del Gatto, F. (2018) ‘Mid-term review – Project GUY-16/0001: Protecting forests through protecting rights in Guyana’. Rainforest Foundation US. Available at: http://www.rainforestfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Protecting-Forests-Through-Protecting-Rights-in-Guyana.pdf

- Forest Peoples Programme (2017) ‘Prensa: Los Pueblos indígenas del Territorio de Vida enviamos un mensaje al mundo’. Media release. Moreton-in-Marsh: Forest Peoples Programme. Available at: https://www.forestpeoples.org/es/global-environment-facility-gef/press-release/2017/prensa-los-pueblos-indigenas-del-territorio-de.

- AIDESEP (Inter Ethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Amazon) and Forest Peoples Programme (2018) ‘The role of international climate finance in securing indigenous lands in Peru: Progress, setbacks and challenges’. Report. Moreton-in-Marsh, UK. Available at: https://www.forestpeoples.org/sites/default/files/documents/A_marathon_print.pdf

- See: Gadeberg, M. (2019) ‘Time to get serious about evaluating REDD+ impacts’. Forests News. Bogor: CIFOR. Available at: https://forestsnews.cifor.org/62303/time-to-get-serious-about-evaluating-redd-impacts?fnl=

- Macqueen, D., Bolin, A., Greijmans, M., Grouwels, S. and Humphries, S. (2020) ‘Innovations towards prosperity emerging in locally controlled forest business models and prospects for scaling up’. World Development (125).

- Macqueen, D. (2019) ‘Vietnamese forest and farm producers work towards more resilient livelihoods and landscapes’. London: International Institute for Environment and Development. Available at: https://www.iied.org/vietnamese-forest-farm-producers-work-towards-more-resilient-livelihoods-landscapes.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (n.d.) FAO’s work with indigenous peoples in forestry. Rome: FAO. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/ca4293en/ca4293en.pdf

- Carino, J. and Sriskanthan, G. (2018). Renewable energy & indigenous peoples. Indigenous Peoples Major Group for Sustainable Development. Available at: https://www.indigenouspeoples-sdg.org/index.php/english/all-resources/ipmg-position-papers-and-publications/ipmg-submission-interventions/93-renewable-energy-indigenous-peoples/file

- Convention on Biological Diversity (2011) Incentive measures for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity: Case studies and lessons learned. Montreal: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-56-en.pdf