Target 18: Traditional knowledge and customary sustainable use

By 2020, the traditional knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, and their customary use of biological resources, are respected, subject to national legislation and relevant international obligations, and fully integrated and reflected in the implementation of the Convention with the full and effective participation of indigenous and local communities, at all relevant levels.

Key messages

- Aichi Biodiversity Target 18 has not been met. Ongoing disregard of the vital contributions of indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs) to biodiversity conservation and sustainable use constitutes a major missed opportunity for the United Nations Decade on Biodiversity 2011¬2020.

- The traditional knowledge and customary sustainable use practices of IPLCs contribute to progress towards implementation of many Aichi Biodiversity Targets but their piecemeal treatment in national biodiversity strategies and action plans (NBSAPs) impedes the full power and potential of IPLC collective actions. This neglect has affected the under-achievement of all 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets, with fundamental lessons remaining to be learnt about securing the future of nature and cultures.

- Some Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) have worked to address this gap, but without reference to the indicators that have been adopted to monitor progress and often without appropriate actions on the ground.

- This gap in implementation and reporting can best be bridged by strategic partnerships with IPLCs to empower them and to renew traditional knowledge and customary sustainable use.

Women making crafts at a workshop using wood from a community-managed forest near Hetauda, Nepal. Credit: Claire Bracegirdle.

Significance of Target 18 for IPLCs

The value of traditional knowledge and customary sustainable use in preventing and addressing biodiversity loss and environmental degradation is well established, and most recently and directly captured in the Summary for Policymakers of the 2019 IPBES Global Assessment on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services:

“Recognizing the knowledge, innovations, practices, institutions and values of indigenous peoples and local communities, and ensuring their inclusion and participation in environmental governance, often enhances their quality of life and the conservation, restoration and sustainable use of nature, which is relevant to broader society. Governance, including customary institutions and management systems and co-management regimes that involve indigenous peoples and local communities, can be an effective way to safeguard nature and its contributions to people by incorporating locally attuned management systems and indigenous and local knowledge. The positive contributions of indigenous peoples and local communities to sustainability can be facilitated through national recognition of land tenure, access and resource rights in accordance with national legislation, the application of free, prior and informed consent, and improved collaboration, fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use, and co-management arrangements with local communities.”1

Tracking progress

The four globally agreed indicators for Target 18 are:

- Trends of linguistic diversity and numbers of speakers of indigenous languages;

- Trends in land-use change and land tenure in the traditional territories of indigenous and local communities;

- Trends in the practice of traditional occupations;

- Trends in which traditional knowledge and practices are respected through their full integration, safeguards and the full and effective participation of indigenous and local communities in the national implementation of the Strategic Plan.2

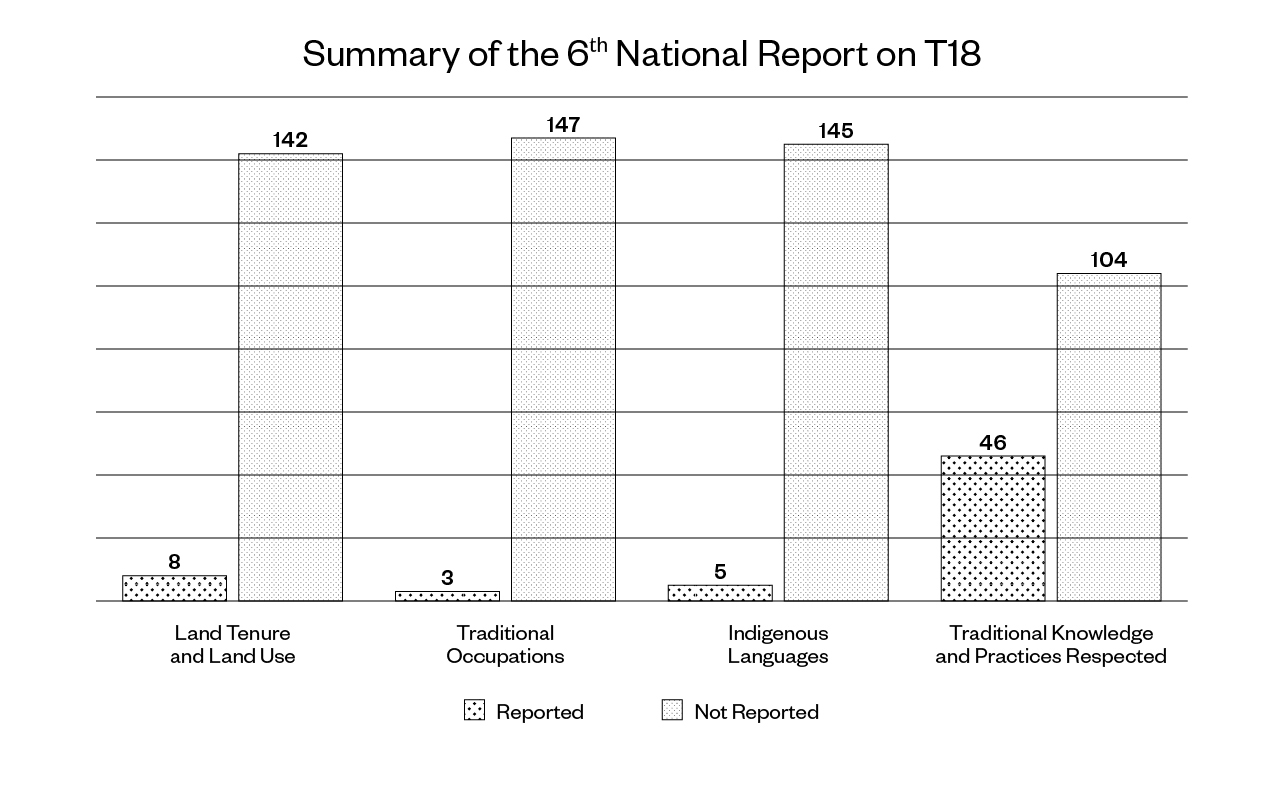

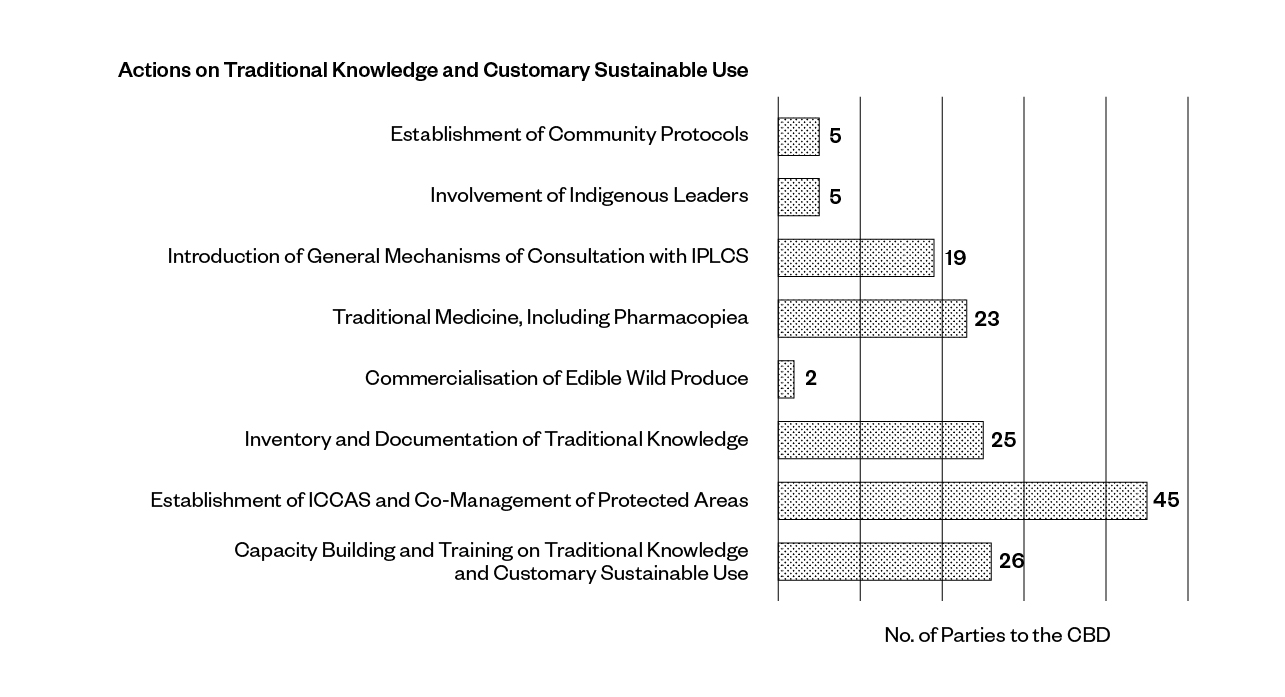

However, an initial analysis of the 150 sixth national reports submitted to and analysed by the Secretariat of the CBD by March 2020 shows that most of them failed to report specifically on these indicators (see Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 5: Reporting on Target 18’s four global indicators in the 150 sixth national reports submitted to the Secretariat of the CBD, March 2020

Figure 6: Actions on traditional knowledge and customary sustainable use, as reported by 150 Parties to the CBD in their sixth national reports to the CBD

An indigenous Shan woman teaches her granddaughter how to make a bamboo fan near Hsipaw, Shan State, Myanmar. Cred it:Ray Waddington.

Thus, as noted by the Secretariat of the CBD3 and the IPBES,4 (see also Table 1), there is insufficient information available to properly assess progress on Target 18. Monitoring of status and trends in the resilience, transmission and revitalisation of traditional knowledge and customary sustainable use is best carried out by IPLCs themselves, being the holders of and experts in their own knowledge. The lack of information highlights the challenge of establishing appropriate and systematic methods and processes to generate the data and evidence base for these indicators of traditional knowledge and customary sustainable use, which have been adopted by Parties of the CBD. Land-use change has been highlighted in the 2019 IPBES global assessment as a main driver of biodiversity loss and the associated loss of indigenous and local knowledge.5 Meanwhile, secure land tenure has been adopted as an indicator under the SDGs to address the eradication of poverty which disproportionately affects women and IPLCs.6 Traditional knowledge and customary sustainable use (including their related indicators) as a cross-cutting thematic programme at the heart of negotiations and contestation between Parties to the CBD and IPLCs encompasses issues such as the legal recognition of their identity and customary tenure of lands and territories, and resource rights.

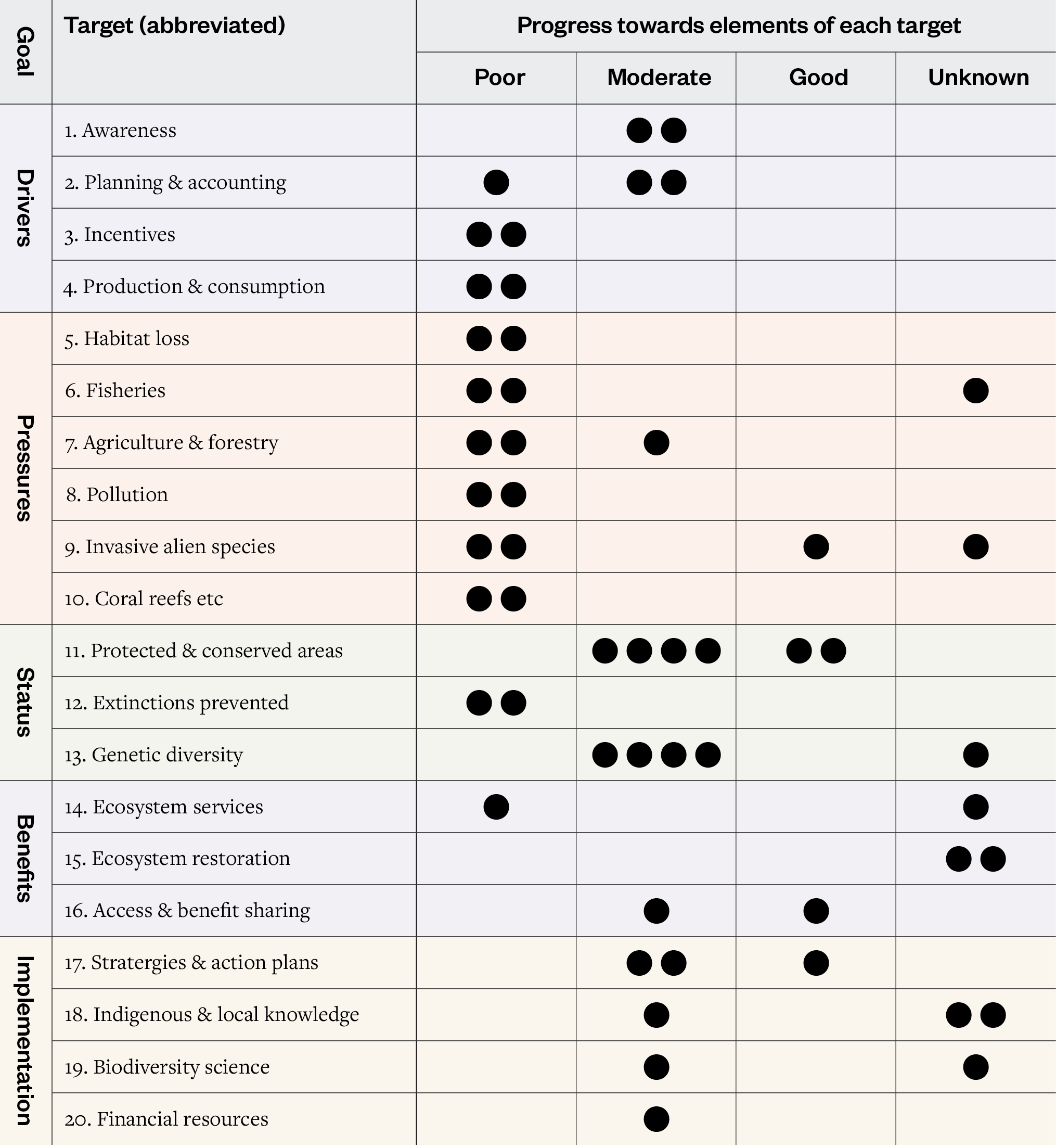

Table 1: Progress towards the Aichi Biodiversity Targets

Scores are based on a quantitative analysis of indicators, a systematic review of the literature, the fifth National Reports to the CBD, and the information available on countries’ stated intentions to implement additional actions by 2020.

Progress towards target elements is scored as:

Good: Substantial positive trends at a global scale relating to most aspects of the element.

Moderate: The overall global trend is positive, but insubstantial or insufficient, or there may be substantial positive trends for some aspects of the element, but little or no progress for others; or the trends are positive in some geographic regions, but not in others.

Poor: Little or no progress towards the element or movement away from it; or, despite local, national or case-specific successes and positive trends for some aspects, the overall global trend shows little or negative progress.

Unknown: Insufficient information to score progress.

Source: IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Summary for Policymakers (2019)7

More positively, overall, respect for diverse knowledge systems and methodologies has been increasing. This is reflected, for example, in the conceptual framework and the work programme of IPBES, and in the United Nations Development Programme’s data ecosystem mapping initiative8. However, such progressive developments in research and science are yet to be manifested in policy and practice at national and sub-national levels.

Contributions and experiences of IPLCs towards Target 18

IPLCs have undertaken numerous initiatives in relation to Target 18, and some of these are described below; for example, in Cameroon and Tanzania, they are monitoring land-use change and securing land tenure; in Japan and Vietnam, they are revitalising culture and language; and in Nicaragua and Hungary they are safeguarding and sustainably using species and ecosystems, and protecting and revitalising traditional occupations.

Negotiating for secure land tenure in Cameroon and Tanzania

In South Cameroon, the Baka communities of Bemba I and Bemba II embarked on a participatory mapping process to document their customary use of resources.9 The maps they have produced show how government permits for forest management units and licences for limestone exploration overlap considerably with their traditional hunting zones, sacred sites, and other areas essential to their customary sustainable use.

“We are not happy with the prospect of being evicted from our villages. Our way of life will be affected by this cement factory. But can a Baka man say no to the implementation of a project that has been decided by the government?”

— Ewondji Bruno, Chief of Bemba II

In July 2019, Bemba I and Bemba II, together with neighbouring communities, used their maps in a meeting with the local government, presenting the likely impacts of a cement factory on their lives. The maps had a significant impact on discussions, and the meeting concluded with an agreement that there needed to be further dialogue, to avoid potential negative impacts for forest communities.

Similarly, in Tanzania the 10,000-year-old hunter-gatherer tribe, the Hadzabe, are the first indigenous community to receive a Certificate of Customary Right of Occupancy in 2011. The certificate is provided for under the Village Land Act of 1999. This was a landmark achievement. The Hadzabe were able to gain leverage through a historic campaign coupled with an innovative carbon-offset scheme through REDD+, community monitoring and inclusive governance.

Revitalising indigenous language in Japan and Vietnam

In April 2019, in Japan, after years of Ainu cultural revitalisation and advocacy, a bill was passed officially recognising the Ainu as indigenous peoples and confirming support for efforts to revive the Ainu culture. This process dates back to the 1997 Ainu Culture Promotion and Dissemination of Information Concerning Ainu Traditions Act. Since then, there have been various activities to revive the Ainu language, which is regarded as crucial to the expression of the Ainu heritage.10

“I myself did not speak [the Ainu language] routinely because it was discouraged, but I was surprised to find I remembered the language unexpectedly … When I was young, I thought Ainu was inferior in the face of discrimination. But now I feel that it was advantageous for me to have acquired the language without knowing.”

— Mutsuko Nakamoto, Ainu writer

In Vietnam, the government has formally recognised traditional languages despite the lack of legal recognition of indigenous peoples. The work of the Vietnamese Indigenous Knowledge Network (VTIK), together with the Centre for Sustainable Development in Mountainous Areas11, led to government commitments to recognise and teach the Mong, Thai and Dao languages and, in March 2016, the Ministry of Culture, Sport and Tourism awarded VTIK members in Son La a certificate recognising the Thai script as National Intangible Inheritance.

These local examples complement global efforts to maintain and revitalise indigenous languages. In 2016, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages. Coordinated by UNESCO, a wealth of activities and actions took place during 2019, culminating in the proclamation of the International Decade of Indigenous Languages (2022–2032) by the United Nations General Assembly on 18 December 201912. In 2020, UNESCO is planning to launch an online platform for the World Atlas of Languages, a repository for linguistic diversity and multilingualism. The International Decade of Indigenous Languages should contribute to a holistic approach to biological and cultural diversity.

Protecting traditional occupations and customary sustainable use

For IPLCs, traditional knowledge, customary sustainable use and conservation are all deeply interconnected, as exemplified by the case studies in Nicaragua (see Box 41) and Hungary (see Box 42).

Box 41: Jadder Mendoza Lewis, Pueblos Indigena Miskitu, Centro de Estudios y Desarrollo de la Autonomía de la Fundación para la Autonomía y Desarrollo de la Costa Atlántica de Nicaragua

Case study: Sustainable use and conservation of the green turtle by the Miskitu indigenous people, Nicaragua

For the Miskitu indigenous people, who inhabit the Caribbean coasts of Nicaragua and Honduras, the green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) is a key natural resource in their food and spiritual systems and conservation efforts, and is a biocultural link that energises social relations, traditional knowledge and livelihoods.

— Read the full case study

Miskitu fisherman with a turtle. In Nicaragua, the Miskitu have maintained the practices of the ancestral use of this resource. Credit: Paul Aguilar.

Box 42: László Sáfián, Shepherd, Hajdúsámson, Hungary and Zsolt Molnár, Ethnoecologist, MTA, Hungary

Case study: Traditional herders are needed to safeguard biodiversity of species-rich grasslands in Central Europe

People don’t see that we herders work for nature: we manage their pastures, we manage weeds, bushes and reeds. People think that all this diversity comes from nature only; they believe that these grasslands would survive without grazing. If herders go, tasty meat will go too.

— Read the full case study

A herder watches over his flock. Credit: Abel Peter.

Opportunities and recommended actions

- IPLCS, including elders, youth, women and men, should initiate and lead a political and technical process on relevant biodiversity and traditional knowledge indicators, addressing methods, tools and mechanisms to monitor progress in implementing local biodiversity strategies and action plans, alongside national, regional and global commitments under the post-2020 biodiversity strategy.

- Governments, in partnership with IPLCs, should adopt enabling policies, laws and mechanisms, including monitoring and reporting modalities, to fully respect and mainstream traditional knowledge, customary sustainable use and benefit-sharing in the implementation of the CBD at the national and sub-national levels.

- IPLCs, governments and other actors should foster and prioritise programmes that enhance the links between biological and cultural diversity, and that build nature-culture alliances.

- Strategic partnerships among IPLCs, governments, international organisations, civil society, NGOs and other actors should be established to support collective actions of IPLCs and their contributions under the post-2020 global biodiversity strategy.

Key resources

- IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). Bonn, Germany: IPBES. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579

- UNESCO Strategic Outcome Document of the 2019 International Year of Indigenous Languages. Available at: https://en.iyil2019.org

- Cultural Survival (2019) Hear our languages – International Year on Indigenous Languages 2019. Available at https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/43-1-hear-our-languages-international-year-indigenous

- Center for Biodiversity & Conservation (2019) ‘Indicators of well-being’. Webinar series. American Museum of Natural History. Available at: https://www.amnh.org/research/center-for-biodiversity-conservation/research-and-conservation/biocultural-conservation-planning/biocultural-approaches/indicators-of-well-being-webinar-series

References

- IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). Bonn, Germany: IPBES. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579

- Convention on Biological Diversity (2016) Decisions XIII/28, Indicators for the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 and the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, CBD/COP/DEC/XIII/28 (12 December 2016). Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-13/cop-13-dec-28-en.pdf

- Convention on Biological Diversity (2019) Informing the scientific and technical evidence base for the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework Addendum Draft Summary For Policy Makers Of The Fifth Edition of the Global Biodiversity Outlook. CBD/SBSTTA.23/2/Add.2. Montreal: Convention on Biological Diversity.

- IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). Bonn, Germany: IPBES. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579

—

See Figure SPM 6, Summary of progress towards the Aichi Biodiversity Targets in: IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). Bonn, Germany: IPBES. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579 - IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). Bonn, Germany: IPBES. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579

- General Assembly resolution 71/313, Global indicator framework adopted, A/RES/71/313. Annual refinements contained in E/CN.3/2018/2 (Annex II), E/CN.3/2019/2 (Annex II), and 2020 Comprehensive Review changes (Annex II) and annual refinements (Annex III) contained in E/CN.3/2020/2.

- IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). Bonn, Germany: IPBES. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579

- United Nations Development Programme (n.d.) Data ecosystems for sustainable development: An assessment of six pilot countries. New York: United Nations Development Programme. Available at: https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/Sustainable%20Development/Data%20Ecosystems%20for%20Sustainable%20Development.pdf

- For more examples of community mapping, including further discussion on the importance of community mapping in addressing land-use change and security of land tenure, see Target 18 in: Forest Peoples Programme, the International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity and the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (2016) Local Biodiversity Outlooks: Indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ contributions to the implementation of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020. A complement to the fourth edition of the Global Biodiversity Outlook. Moreton-in-Marsh, England. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/gbo/gbo4/publication/lbo-en.pdf

- Sunuwar, D.K. (2020) ‘Ainu people reclaim their rights’, Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine 44(1).

—

Hirano, K. (2002) ‘Efforts to preserve Ainu language gain momentum’. Japan Times. Tokyo: The Japan Times. Available at: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2002/06/15/national/efforts-to-preserve-ainu-language-gain-momentum/#.Xoip6dNKj0F - For more information on the Centre for Sustainable Development in Mountainous Areas, see: https://www.iwgia.org/en/iwgia-partners/55-centre-for-sustainable-development-in-mountainous-areas-vietnam

- General Assembly resolution 74/135, Rights of indigenous peoples, A/RES/74/135 (18 December 2019).