Target 7: Sustainable agriculture, aquaculture and forestry

By 2020 areas under agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are managed sustainably, ensuring conservation of biodiversity.

Key messages

- Over the past decade concerns have been growing about global approaches to food and agricultural policy, and about the need to promote the role of indigenous peoples, small-scale farmers and producers, and local farm and forest enterprises.

- Bringing agriculture, aquaculture and forestry under sustainable management requires mainstreaming and empowerment of IPLCs as central actors in transforming rural development.

- Long-standing laws, policies and programmes that have promoted the growth of a globalised agro-industrial system of production and consumption, causing the widespread decline of biodiversity and the erosion of local management systems and customary sustainable use, need to be reformed.

Significance of Target 7 for IPLCs

IPLC production systems based on agroforestry, fishing, hunting and pastoralism constitute a large part of rural economies, which are hugely important for both their subsistence and market values.1 However, customary land use and resource management systems have been under pressure from large-scale commodity production linked to global supply chains, to the neglect of small-scale producers.2 The impact on IPLCs of export-led economic strategies has been dispossession of their territories, lands, forests and other natural resources; impoverishment; exploitation of their knowledge; and marginalisation in decision-making over matters affecting their futures.

Bringing agriculture, aquaculture and forestry under sustainable management requires mainstreaming and empowering IPLCs to be central actors in rural development, and reversing long-standing laws, policies and programmes that have resulted in the decline of biodiversity and the erosion of indigenous and local knowledge in rural landscapes. The sustained, local, collective actions of IPLCs combined can have a transformative global impact.3

Box 12

UN Decade of Family Farming: A global plan of action

The Global Plan of Action adopted by the UN Decade of Family Farming 2019–2028 covers “all types of family-based production models in agriculture, fishery, forestry, pastoral and aquaculture and includes peasants, indigenous peoples, traditional communities, fisher folks, mountain farmers, forest users and pastoralists”.4

It acknowledges family farming as the predominant form of food and agricultural production in both developed and developing countries, producing over 80 per cent of the world’s food in terms of value.

“Beyond food production, they [farming families] simultaneously fulfil environmental, social and cultural functions, preserving landscapes and biodiversity and maintaining community and cultural heritage.

“[… ] As widely recognized, the current food and agricultural system is largely responsible for deforestation, water scarcities, biodiversity loss, and soil depletion along with high levels of greenhouse gas emissions, which have significantly contributed to climate change. Today’s food production and consumption have been shifted from their culturally and socially embedded systems towards a system disconnected from local ecological and social systems. In order to meet the needs of present and future generations, it is essential to accelerate a transition towards more sustainable food and agriculture systems that can simultaneously provide economic and social opportunities, while protecting the ecosystems upon which agriculture depends and respecting the cultural and social diversity of territories. Territorial development needs to be reconnected with the people (and families) who carry out the productive activity, with their practices, their values, and with the knowledge traditionally and locally determined.”

Contributions and experiences of IPLCs towards Target 7

Les peuples autochtones et les communautés locales promeuvent l’innovation dans les systèmes locaux de production afin de répondre aux besoins changeants de leurs communautés, notamment de nouvelles formes de moyens de subsistance et activités génératrices de revenus5 . Ils forment également de nouveaux réseaux de producteurs à petite échelle qui incarnent le message « manger des produits locaux et de saison »— un enseignement important pour l’ensemble de la société alors qu’elle s’engage dans des transitions des systèmes alimentaires, de production et de consommation. Investir dans des entreprises sociales communautaires constitue une autre voie vers la réalisation de l’objectif 7.

“Indigenous people are here to maintain survival as a plausible goal. Subsistence is a moral relationship with nature. In many ways, it is the indigenous cultures’ relationship to the earth that represents the only real hope for the long-term survival of people on any scale in the world. Subsistence means that there’s a forest here today, and we find a way to make a living here. Then tomorrow, there’s still a forest here. That’s subsistence.”6

— John Mohawk, respected indigenous teacher from North America

Box 13: Brenda Asuncion, Kevin K.J. Chang, Miwa Tamanaha; Kuaʻāina Ulu ʻAuamo

Restoring the wall of Waia‘ōpae fishpond, Lānai, Hawaii. Credit: Scott Kanda, courtesy of Kua‘āina Ulu ‘Auamo.

Case study: Loko iʻa: Indigenous aquaculture and mariculture in Hawaiʻi, USA

Loko iʻa are advanced, extensive forms of aquaculture unique to Hawaiʻi. While techniques of herding or trapping adult fish in shallow tidal areas, in estuaries and along their inland migration can be found around the globe, Hawaiians have developed fishponds that are technologically unique, advancing the cultivation practice of mahi iʻa (fish farmer).

— Read the full case study

Box 14: Nutdanai Trakansuphakon7, Pgaz K’Nyau Association for Sustainable Development

Case study: Pgaz K’Nyau community social enterprise as alternative livelihoods for young generations, northern Thailand

The Pgaz K’Nyau (Karen) practise rotational farming as a self-reliant economy for our own food consumption. But, today, we also need cash incomes for our expenses in everyday life. The Pgaz K’Nyau Association for Sustainable Development works with Pgaz K’Nyau communities on community social enterprise because young people are migrating to work in urban areas, leaving a gap between elders and youth.

— Read full case study

A man practices rotational farming in a Karen community, Thailand. Credit: Chalit Saphaphak.

Emerging initiatives

Farmer networks such as La Via Campesina (the Peasant Way) are reclaiming the term peasant and building a shared peasant identity across national borders and cultures. Their main concerns are: promoting food sovereignty; agrarian reform; people’s control over land, water and territories; popular peasant feminism; participation of youth in agriculture; human rights, including of migrant workers; promoting agroecology and peasant seed systems; and resisting free trade and the power of transnational corporations.

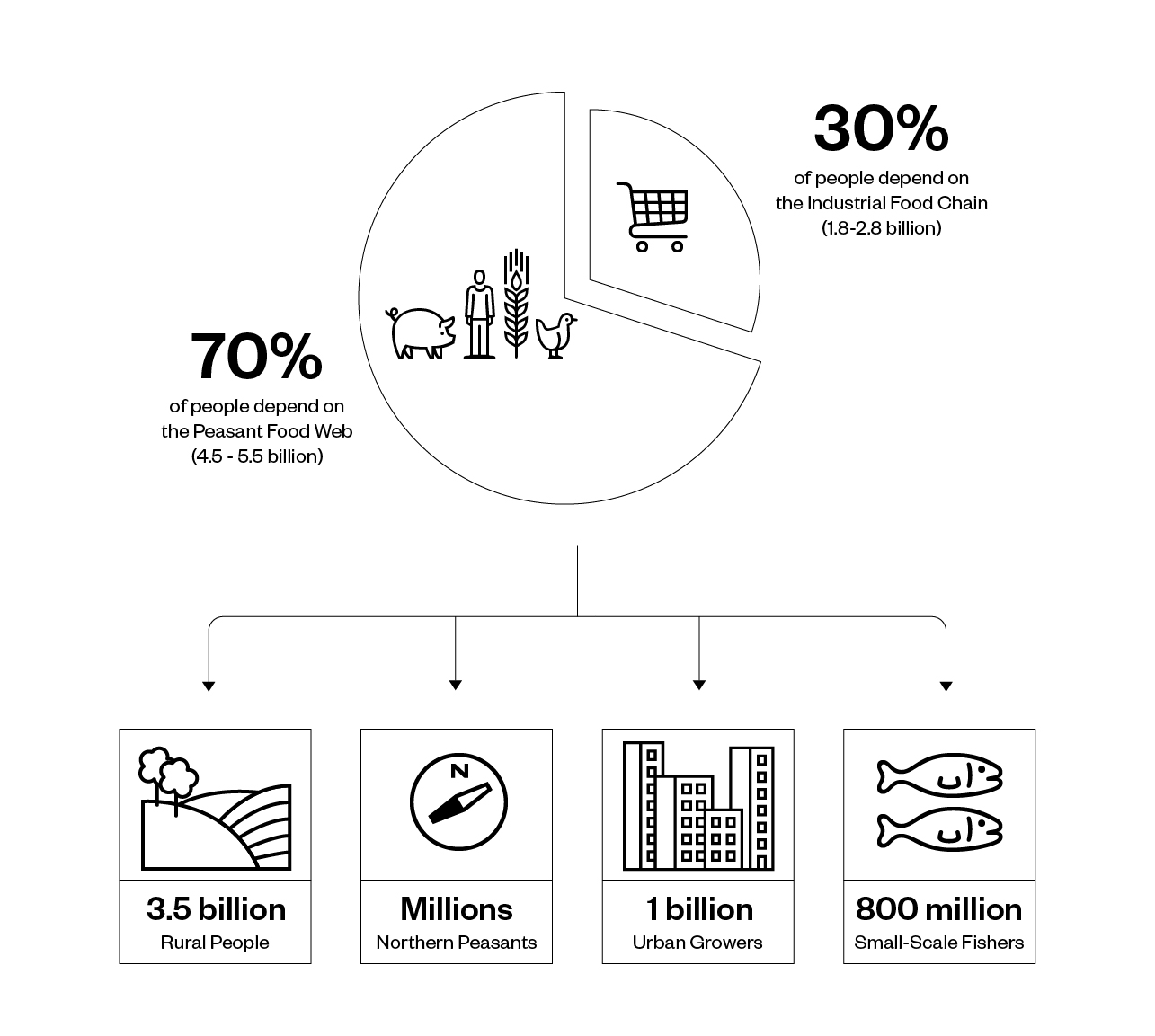

The peasant food web (see Figure 2) 8 has been defined as the web of small-scale producers—usually family- or women-led, and including farmers, livestock-keepers, pastoralists, hunters, gatherers, fishers, and urban and peri-urban producers—who together feed 70 per cent of the world’s people. Rural peoples who look to famine foods in the seasons of scarcity before harvest will survive thanks to the peasant food web’s protection of agricultural biological diversity.

Multiple initiatives and instruments provide fertile opportunities for including IPLCs as central actors in the transition towards sustainable agricultural and food systems.

UN initiatives include:

- UN Decade of Action on Nutrition 2016–2025

- UN Water Action Decade 2018–2028

- UN Decade of Family Farming 2019–2028

- UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration 2021–2030.

Young Karen women dry tea leaves. Credit: Visarut Sankham.

Policy instruments include:

- Voluntary Guidelines to Support the Progressive Realization of the Right to Adequate Food in the Context of National Food Security10;

- Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security11;

- Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication12;

- UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas13.

Securing legal recognition of customary tenure of IPLCs to their lands, territories and resources is critical for progress in sustainable agriculture, aquaculture and forestry, and also for achieving poverty eradication, conserving biodiversity, and climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Opportunities and recommended actions

- IPLCs should ensure the full and effective participation of women and men, elders and youth, and people with disabilities, in their ongoing revitalisation of customary resource management and sustainable use practices.

- Governments must protect IPLC territories and smallholder landscapes from incursions by agro-industrial production systems.

- Governments must develop joined-up national strategies and action plans, under the various UN decades—Family Farming; Action on Nutrition; Water Action; Ecosystem Restoration—while implementing the CBD Plan of Action on Customary Sustainable Use of Biological Diversity, including through strengthening IPLC organisations and networks engaged in ecological restoration and community livelihoods; and providing greater support and investment in smallholder production, traditional occupations and community social enterprises.

- Governments, UN agencies, IPLCs and research organisations should establish partnerships to improve the collection of data (local, national and global statistics) on the contributions of small-scale producers towards their recognition in policy and actions.

- Development funders and donors, in particular the development banks and major foundations, should change their funding approach, reallocating funding towards the agroecological transformation of the food system, including revitalisation of indigenous food systems.

- All actors should promote farmers’ rights and support farmers to continue to maintain, develop and manage genetic resources, including IPLC in-situ gene banks for traditional seed production, and recognise and reward them for their indispensable contributions to the global pool of genetic resources.

Key resources

- Forest and Farm Facility: http://www.fao.org/forest-farm-facility/en/

- ETC Group (2017) Who will feed us? The Peasant Food Web vs The Industrial Food Chain, 3rd ETC Group. Available at: https://www.etcgroup.org/whowillfeedus

- HLPE (2019). ‘Agroecological and other innovative approaches for sustainable agriculture and food systems that enhance food security and nutrition’. HLPE 14. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome. Available at: http://www.fao.org/agroecology/database/detail/en/c/1242141/

- The International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative: https://satoyama-initiative.org/

- FAO and IFAD (2019) United Nations Decade of Family Farming 2019-2028: Global Action Plan. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available at: http://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1195619/

Kahina Pōhaku fishpond in Moloka‘i, Hawaii. Credit: Scott Kanda, courtesy of Kua‘āina Ulu ‘Auamo.

- Verdone, M. (2018) ‘The world’s largest private sector? Recognising the cumulative economic value of small-scale forest and farm producers’. Gland: IUCN, FAO, IIED, AgriCord. Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/47738

- International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (2016) ‘From uniformity to diversity: a paradigm shift from industrial agriculture to diversified agroecological systems’. Bonn: International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food systems. Available at: http://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/UniformityToDiversity_FULL.pdf

References

- High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. (2019) Agroecological and other innovative approaches for sustainable agriculture and food systems that enhance food security and nutrition. Rome: High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/ca5602en/ca5602en.pdf

- Satoyama Initiative (n.d.) The International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative. Tokyo: Satoyama Initiative. Available at: https://satoyama-initiative.org/

- Verdone, M. (2018) The world’s largest private sector? Recognising the cumulative economic value of small-scale forest and farm producers. Report. Gland: IUCN, FAO, IIED, AgriCord. Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/47738

—

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (n.d.) Forest and Farm Facility. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available at: http://www.fao.org/forest-farm-facility/en/ - FAO and IFAD (2019) United Nations Decade of Family Farming 2019-2028. Global Action Plan. Rome: FAO and IFAD. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/ca4672en/ca4672en.pdf

- International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (n.d.) International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems. Bruxelles : International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems. Disponible sur : http://www.ipes-food.org/

- Mohawk, J. (2006) ‘Subsistence and materialism’ in Mander, J. and Tauli-Corpuz, V. (Eds.) Paradigm wars: Indigenous peoples’ resistance to globalization. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

- Nutdanai Trakansuphakon is a new-generation activist and social worker, working to add value to local non-timber forest products of Hin Lad Nai and other communities as alternative social enterprises.

- ETC Group (2017) Who will feed us? The Industrial Food Chain vs. The Peasant Food Web, 3rd Edition. ETC Group. Available at: http://www.etcgroup.org/sites/www.etcgroup.org/files/files/etc-whowillfeedus-english-webshare.pdf

- ETC Group (2017) Who will feed us? The Industrial Food Chain vs. The Peasant Food Web, 3rd Edition. ETC Group. Available at: http://www.etcgroup.org/sites/www.etcgroup.org/files/files/etc-whowillfeedus-english-webshare.pdf

- FAO (2005) Voluntary guidelines to support the progressive realization of the right to adequate food in the context of national food security. Adopted by the 127th Session of the FAO Council. Rome: FAO.

- FAO and CFS (2012) Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security. Rome: FAO. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i2801e.pdf

- FAO (2015) Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication. Rome: FAO. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4356en.pdf

- General Assembly resolution 73/165, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas, A/RES/73/165 adopted on 17 December 2018. Available at: https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/73/165